Rijeka is a city in Kvarner, a relatively clean and biodiverse bay lying between Istria and Primorje Gorski Kotar County of Croatia. Rijeka is a city of rich history. It has been a part of several states in the 19th and 20th Century, as well as, briefly, an independent state itself. In the second half of the 19th Century, it was a bustling industrial, commercial and technological center and a home to an ethnically and religiously diverse population. It was the testing ground for the first experiments of Italian fascism. It was a relevant port with growing industry and vibrant cultural life during Yugoslavia. And then, as Croatia became independent, it became just another small city, a peripheral town in a peripheral state.

And yet, Rijeka just couldn’t let go of its dreams of greatness. In the last two decades in particular, Rijeka became a city over-invested in its own mythology of a unique and great city on the brink of becoming. This mythology is largely sustained by an unbroken continuity of rule by center-left city government in a dominantly right-wing Croatia, and by the attendant generally social-liberal culture of its citizens. To its citizens, Rijeka feels like an open European cosmopolis, but looks like a dirty, abandoned post-industrial shrinking seaside town.

This disconnect weighs in on many decisions by its city government, and it usually leads to unfortunate policies. The most recent example of this was its European Capital of Culture (ECoC) title, featuring a program betting almost exclusively on an extravagant, overcomplicated, and outdated vision, which had little to do with actual cultural life and needs of the city and which the city was poorly equipped to implement. The title predictably led to an increase in gentrification and an exodus of many exploited and burned-out artists and cultural workers who were critical to saving the ECoC from complete disaster.

Desire for living large – trumps ecocide?

The current installment of Rijeka’s search for greatness will lead to the environmental collapse of Kvarner bay. The plan is to sell the city center coastline to an entrepreneur for the purpose of building a yacht port. The idea is applauded unanimously by decision-makers, tourism professionals, and, crucially, citizens of Rijeka. Any dissent to the idea is met with incredulous dismissal – why would somebody want to stop Rijeka from becoming great again? And more precisely, a popular rebuttal to dissent to giving away the city to private business is – what is there to lose? An attempt by a local chapter of a green-left party to pressure the city government to reconsider or change their decision due to a shady contract signed with the entrepreneur, has largely been ignored by both the officials and the public.

There is only one future possible: the one in which the yacht business, predictably, destroys the bay. We who live today in Rijeka are the last generation to witness the Kvarner bay as a place of diverse life, beauty and leisure. What follows is a decade of easy money for tourism which will pollute the sea and decimate its wildlife, and then abandon Rijeka in search of a new naive little town desperate to look like a grand city. The story is obvious and well known. And there is, at this point, nothing to be done about it.

We write this because it illustrates a relevant aspect of the politics of the climate crisis. Despite the years of media presence, ecological considerations rarely, if ever, superseded the popular imaginary of an investor with a great vision bringing growth and glitter to a locality. In Rijeka, this imaginary is fed by its citizens’ hunger for the city to look how it feels to them: by their dreams of Rijeka becoming a wealthy cosmopolitan European city, by any means necessary. While Rijeka is, admittedly, not a particularly bad city to live in as is – it has clean water, clean air, decent food, and it is quite safe – these things don’t feel sufficient to its citizens and decision-makers. Just a small taste of living large will be worth poisoning their waters and soil.

The transition needs new dreams

There can be many lessons drawn from this. Some are simply defeatist. But one might point to an underdeveloped, and thus arguably opportunity-filled, aspect of the (left) politics of the climate crisis: the transition needs new dreams. The left politics of the climate crisis tends to illuminate the nightmares, and work intensely and wholeheartedly on particular, and outstandingly relevant, solutions. This is doubtlessly admirable and crucial. But it never translates into new habitual political reasoning of citizens, which is nurtured by dreams of how life becomes better, and sometimes, of how cities become greater.

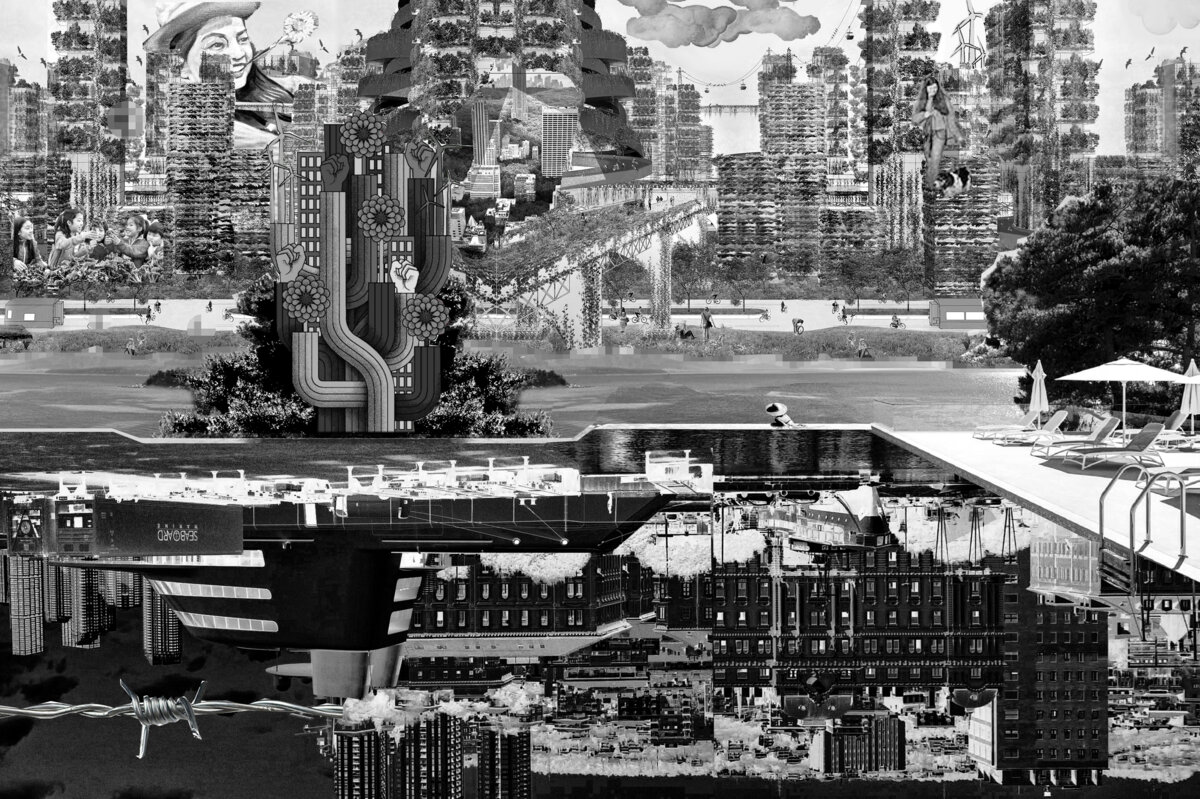

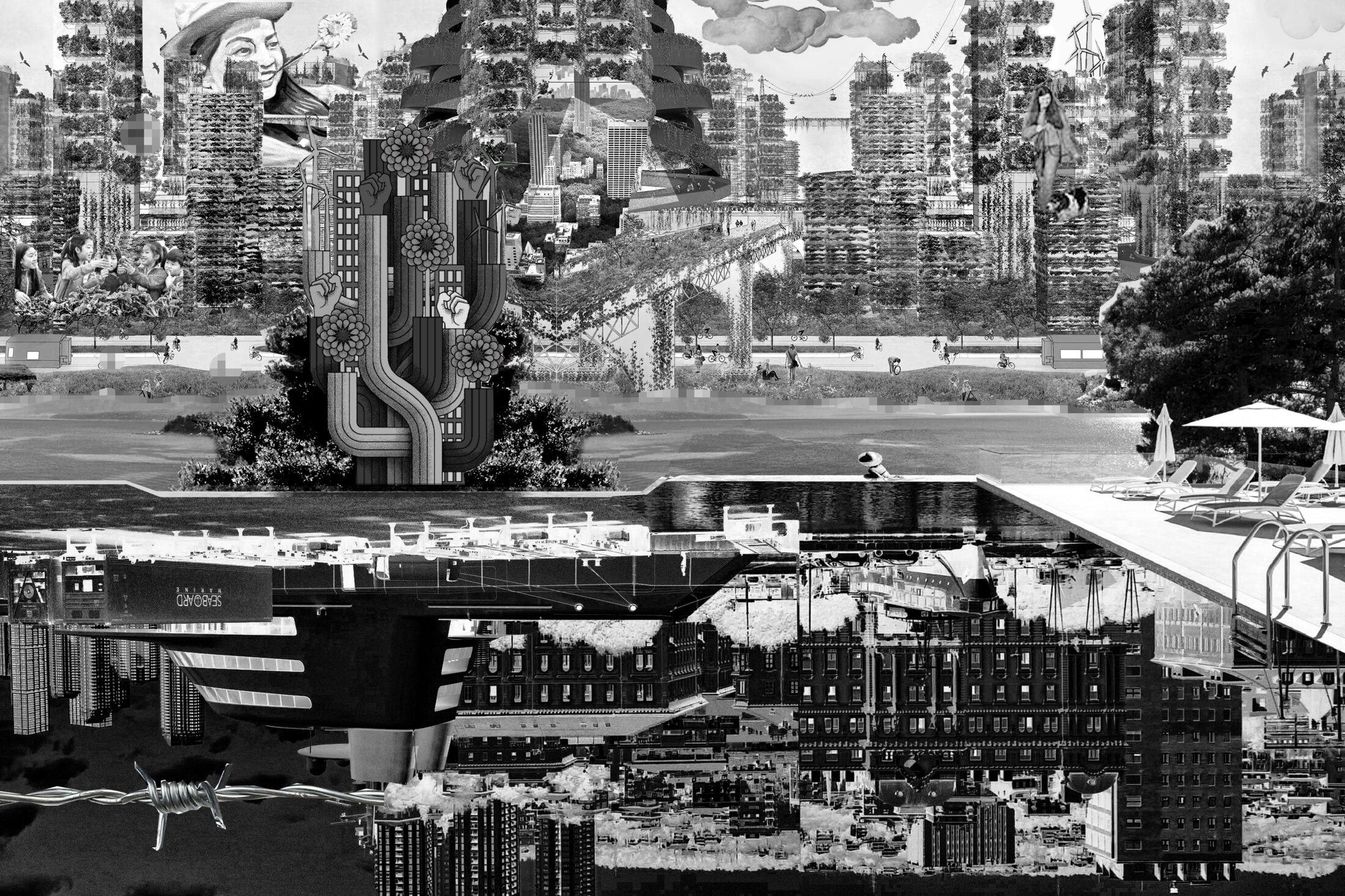

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

It is wrong to discard dreams as mere indulgence, sentimentality. They are heuristics and frames for navigating complexity, tools for robustly organizing opinions and attention. Without new dreams, all that people have are the old desperate dreams to cling onto when they need to make decisions or support what they believe will make the future better. And people do need to feel that the future will be better: they are overworked and underpaid, or they are young and want to imagine that their life can be interesting and valuable, or they have children and grandchildren and want to imagine them living in a better city. Their reliable engagement at critical points in the political process will always depend on what makes them feel that the future can be good.

To satisfy this need, all they now have are the left over pieces of exhausted dreams of private investors: yachts, tourists, and noughties-style versions of leisure centers, replacing the current parking lots along the city center coastline. Or, in other contexts, the equally exhausted dreams of a messiah, who will be the voice of the “heartland” people, restoring their communal ties, in-group solidarity and traditions.

The proper – just and comprehensive – transition requires several fundamental changes: economic, political, technological, and epistemic. But it also requires new dreams which make some choices obvious and resistance to them unbelievable and silly. New dreams, which make climate justice a no-brainer in the same way that sacrificing Kvarner bay is for Rijeka citizens today.

****

This text is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “After Extractivism” text series; its German version is available on Berliner Gazette. You can find more contents on the English-language “After Extractivism” website. Have a look here: https://after-extractivism.berlinergazette.de

Sanja Bojanić

Sanja Bojanić is a researcher immersed in philosophy of culture; media and queer studies, with an overarching commitment to comprehend contemporary forms of gender, racial and class practices, which underpin social and affective inequalities specifically increased in the contemporary societal and political contexts. She firstly studied philosophy and tailored her interests at the University of Paris 8, where she obtained an M.A. in Hypermedia Studies at the Department of Science and Technology of Information, and an M.A. and Ph.D. at Centre d'Etudes féminines et d'etude de genre, a processes that ultimately led to interdisciplinary research based on experimental artistic practices, queer studies, and particularities of Affect Theory. Her research and scientific work are fostered through various projects funded by EU Commission and private foundations. Author and editor of several books and manuals, she published over thirty peer-reviewed papers on topics related to her field of expertise.

Marko-Luka Zubčić

Marko-Luka Zubčić is a Fellow of Center for Advanced Studies South East Europe and assistant lecturer in epistemology at Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Rijeka. He holds a PhD in philosophy from University of Rijeka. He works in social and institutional epistemology, with focus on ignorance, pluralism, collective epistemic virtues, and epistemic reliability in institutional and organizational design. His work is published in Ethics & Politics, Philosophy & Society, and Synthese, and he co-edited the Special Issue of Phenomenology and Mind on the topic of non-verbal normativity with Olimpia Loddo and Sanja Bojanić. He is dedicated to applying the insights of institutional epistemology in the real world. He conducts workshops in participatory policy-making, and works on the design of instruments for utilization of diversity, collective and distributed intelligence for policy-making and problem-solving. He provides communications and strategy consultancy for NGOs working on child poverty and food security.