Private View and Exhibition

I was very recently pleased to be invited to the private view of the exhibition "Ai Weiwei: The Liberty of Doubt" which consists of twenty one free-standing exhibits and a twenty-second, "British Museum Case" containing eight further exhibits. The exhibits are accompanied by three of the artist's documentary films: Human Flow (2017) which deals with human migration, Coronation which documents the recent Wuhan lockdown following the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, and Cockroach (2020) which records Hong Kong's 2019 protests and the unprecedented police violence that ensued.

The Fake

The overarching theme of the exhibition relates to the falseness and the fake of our globalized world, of which contemporary China is only, but nevertheless an essential part. This was a globalization that Guy Debord theorized towards the end of the last century in his revisiting of the Society of the Spectacle (1967) entitled Comments on the Society of the Spectacle (1988).

Citing the German Hegelian philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872), Debord ruminates on Feuerbach judgement that his time preferred “the image to the thing, the copy to the original, representation to reality.” That judgement writes Debord "has been entirely confirmed by the century of the spectacle, and in several domains where the nineteenth century preferred to keep its distance from what was already its fundamental nature: industrial capitalist production. At that time, "the bourgeoisie had widely spread the rigorous spirit of the museum, the original object, precise historical criticism, the authentic document." But nowadays, "the artificial tends to replace the true everywhere." It is a world in which Roman statues has been replaced by plastic replicas: "In short, everything will be more beautiful than before, so as to be photographed by tourists.

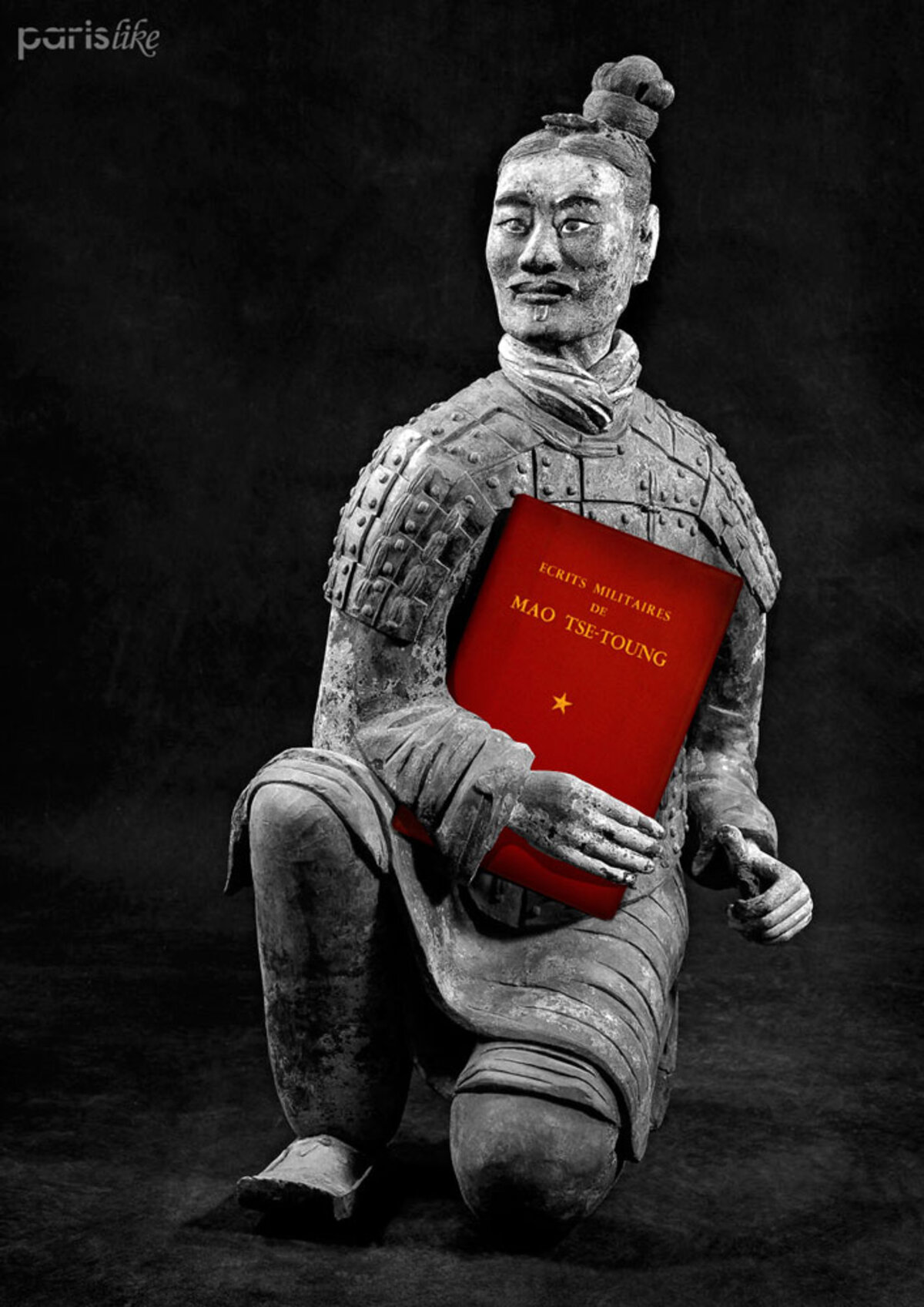

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

Debord also subscribed to the theory, as do several serious critical sinologists who maintain their freedom to doubt, that the ranks of terracotta soldiers in the approaches to the imperial tombs at Xi'an, are fakes. It is worth quoting Debord's comment at length:

The highest point has without doubt been reached by the Chinese bureaucracy’s laughable fake of the great statues of the industrial army of the First Emperor, which so many visiting statesmen have been taken to admire in situ. Since one could mock them so cruelly, this thus proves that in all the masses of their advisors, there was not a single individual who knew the history of art, in China or anywhere else.

Debord concludes with words that sum up our current world political spectacle, when he writes, "for the first time, it is possible to govern without any artistic knowledge, nor any sense of the authentic or the impossible," which justifies the conclusion that "the naive dupes of the economy and the administration will probably lead the world to some great catastrophe."

This is the world addressed, demonstrated and doubted by Ai Weiwei's exhibition.

Getting to Know Ai Weiwei's Universe

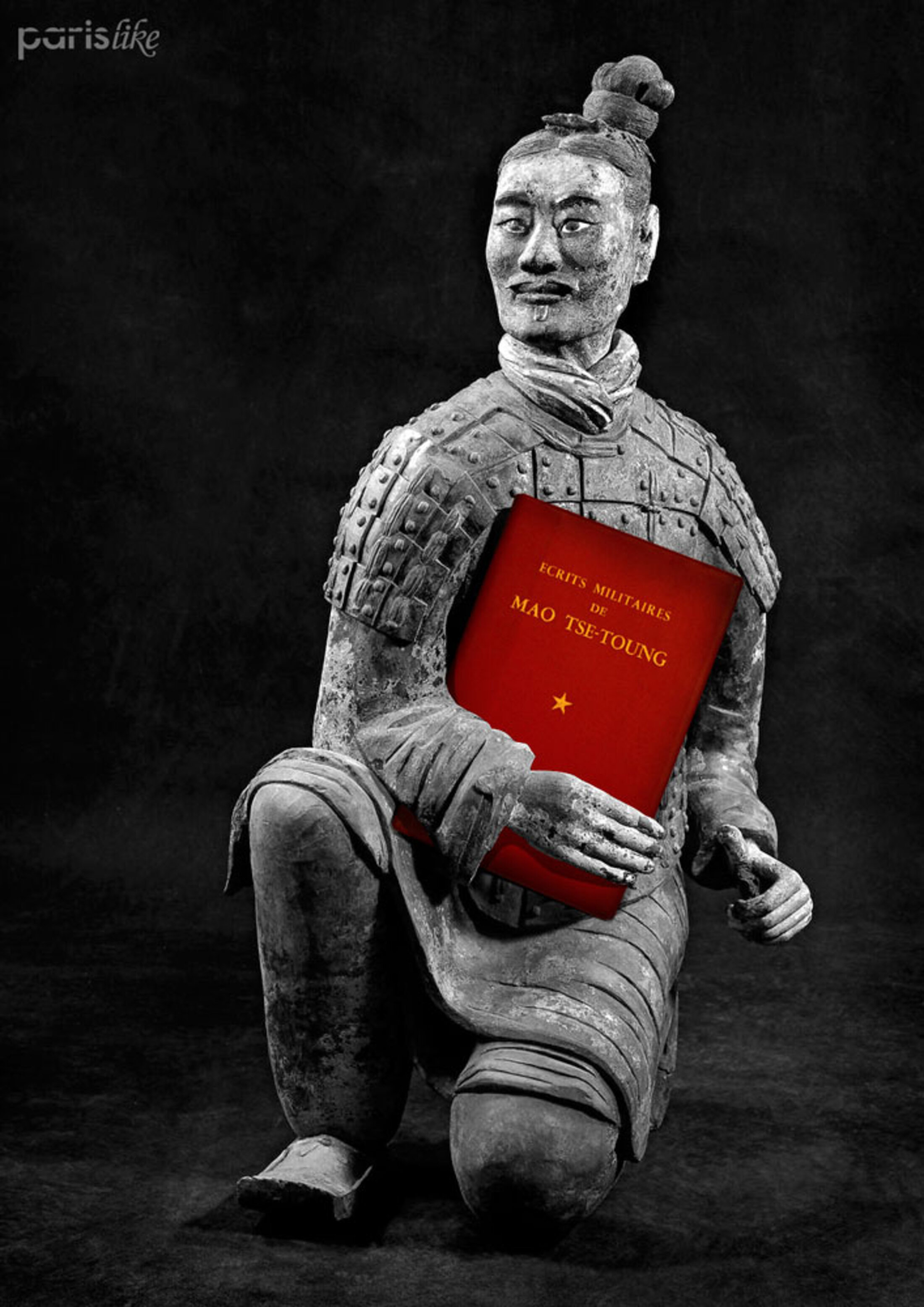

I have no way of knowing how the guests appreciated the work on display. I am in a sense too close to the background world of Ai Weiwei's universe, too much a privileged reader of his work. As a cultural historian of China who first set foot in China over 40 years ago, I brought a certain cultural baggage to the act of seeing the exhibition. Although I am not a close acquaintance of the artist, I have followed his life and career. I also know well the life and work of his late father the poet Ai Qing, whom I once met in Beijing. Or rather, I thought I knew. Reading Ai Weiwei's recent biographical/autobiographical 1000 Year of Joys and Sorrows, I realised there was much I did not know, especially the detail of the narrative of misery when Ai Weiwei's and his father's lives were intertwined in the suffering of daily survival of desert exile. Anyone genuinely interested in beginning to understand the exhibition "Ai Weiwei: The Liberty of Doubt" must read that book. Unfortunately, I doubt that many of the spectators or professional critics have read that book, or otherwise equipped themselves to grapple with Ai Weiwei's universe.

Agrandissement : Illustration 2

Perhaps, I am being too harsh. People are no longer taught that reading a poem, watching a performance, looking at a piece of art requires the reader/spectator to work, to invest in the act of reading and looking. To go beyond surface impressions requires what in the world of finance is known as "due diligence". Facile judgments of Ai Weiwei's "intentions", that several critics in the press have indulged in, may seem clever, but such judgments are not grounded in any attempt to understand, and to have a readership understand, the context of Ai's work. Rather they are the product of haughty ignorance: ungracious, ill-informed, under-researched.

Détournement

In the absence of a knowledge of the context, an alternative means to access the spirit of the exhibition may be provided by an acquaintance with the situationist practice of détournement. While such theoretical knowledge is not essential, it nevertheless helps the visitor to grasp what is going on more swiftly. Détournement is the appropriation of a style, a form, a text, turning it to give it a different or supplementary meaning from its intended or habitual one. In Ai's exhibition there are numerous such examples. For instance, there is "The Chair for non-attendance" (exhibit 19) with its additional arm across the seat alluding to the Chinese state's preventing Ai's presence at a Stockholm film festival. Guy Debord and his group used purloined popular comic strips, placing radical discourse in the speech bubbles. Ai appropriates Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, originally a Yuan dynasty cosmopolitan fusion of diverse Asian cultures, but which came to be seen as quintessentially "Chinese". Ai uses this dominant porcelain tradition of the Ming and the Qing to tell the story of migration: War, Ruins, the Journey, Crossing the Sea, Refugee Camps, Demonstrations. The plates evoke the story of The Odyssey, but also the contemporary lived experience that we see in his documentary film Human Flow.

Agrandissement : Illustration 3

Détournement is not the production of fakes, but rather a blatant exposure of an object's contemporary vacuity and the injection of new sometimes jarring meaning. The new LEGO iteration of Ai's 1995 "Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn" (exhibit 6) may be seen as an auto-détournement of the artist's own work, another take on a now reified act.

Agrandissement : Illustration 4

Hong Kong and Britain's Responsibility

As I sat and watched Cockroach, a name coined by pro-Chinese government elements to denigrate the protesters, I also observed dozens of people in small groups wander in and stay for a few minutes and then leave. Naturally, if they didn't know the history behind the film, all they saw were a few late middle-aged Chinese talking-heads, followed by students throwing Molotov cocktails and the attempts of the police to arrest them. Those talking-heads, Martin Lee, Albert Ho, Emily Lau, honourable and persistent defenders of democratic freedoms and basic human rights, ought to be household names in the UK, but they are not. Of course, the spectators perhaps had already read reviews of the film, such as the very favourable critique by The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw. However, what is missing from that review is the long back story into which is woven Britain's historical legacy. Hong Kong is not just another stick – like the dilemma of the Uyghurs or the Tibetans – with which to beat the Chinese authorities. Hong Kong, it is also a historical and current British responsibility. Of those who viewed the film even for a few minutes, one wonders how many pondered that responsibility and the part the British state, but also the British people, have played in how Hong Kong came to be where it is now? The story of Hong Kong, an abandoned colony, is part of the historical scandal of British imperialism in "British Asia", alongside the colonisation of the sub-continent, and the Opium Wars and the ensuing imposed addiction to that pernicious drug. As I wrote in "Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo and David Cameron's poppy" (Postcolonial Studies, 14 (2011), 4), it is too easy to forget history and focus merely on the behaviour of "the Chinese" while failing to account for Britains's own human rights record since the rise of nation-state colonialism, and to leave unaddressed the historical reality of Britain in China.

Coda

An opening event is not the same as a daytime museum visit. The event was very well attended, with perhaps between 150 and 200 people in the building an hour after the wine started flowing. Of course, the motivation for being at a private view does not necessarily coincide with that of visiting an exhibition alone to see, read and try to make sense of what one sees. Opening nights are as much about seeing others and being seen as looking at art; the spectators being at the same time the observers and the observed. Indeed, this particular private function seemed as much a celebration of the post-COVID return to normal of the University of Cambridge's Kettle's Yard as it was a show of the work of Ai Weiwei. At one point during the mainly self-congratulatory speeches Ai Weiwei seemed almost lost in the crowd. He was the star of the show swallowed up by a public buoyed by post-COVID euphoria.