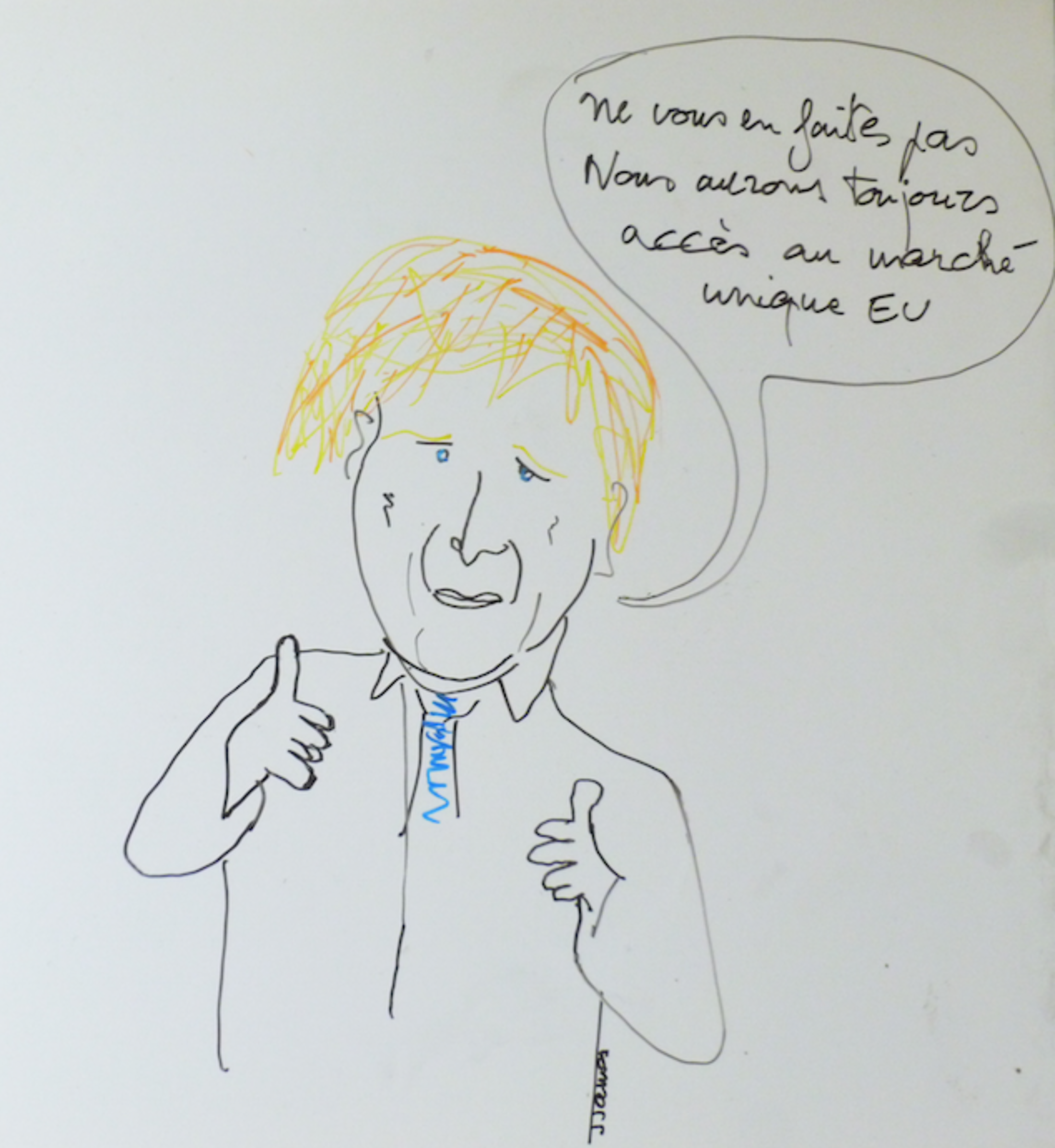

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

Boris Johnson the colourful guy could well be Britain's next prime minister

When British Prime Minister David Cameron turned down a chance last month to debate Boris Johnson on whether Britain should leave the European Union, he claimed he didn't want to reduce the campaign to a "Tory psychodrama." I suspect he didn't want to risk being humiliated on TV by the quick-witted debater he's known since their college days. Before Johnson was Cameron's arch rival on the Brexit debate and before he was mayor of London, he was a student debater and president of the Oxford Union.

That's where I first met the man who's now a leading contender to replace Cameron as prime minister. Johnson was one of the more memorable participants at the World Universities Debating Championship in Dublin in 1987. From the unruly blond hair made more visible by standing on tables to the outsized delight he took in seeing top US teams pitted against each other in the first round, Johnson was a character. He didn't win that year—a team from Glasgow did—but he won numerous fans with his wit and willingness to stir the pot.

I thought about that as I watched Johnson argue eloquently for Brexit, despite dire warnings from US President Barack Obama, European leaders, and his old friend who leads his party and his country. The negative economic consequences of such a move were clear. But Johnson spoke of national liberation and breaking out of jail while joking about opponents and posing with fish. Cameron grimly warned of disaster and said it would be immoral to vote for Brexit. (If so, then why put the issue to a national vote?) That's no way to win over the crowd.

When I started impromptu debating at the University of Toronto, I was given two "truths" about foreign competition: Americans like to prepare and twist a resolution to the topic they want; Brits win on wit. The first philosophy spawns Ted Cruz; the second, Johnson. Having seen both men debate on the college circuit (facing Johnson and judging Cruz), it's clear that either approach can create a compelling argument. Impromptu debating—where you typically get 10 minutes to prepare for a debate and mere seconds for a speech—is a fabulous sport for teaching you to think quickly on your feet. You learn to crack jokes and argue any side of an issue.

But saying what's needed to win is different than saying what's right. Johnson’s rhetorical skills have helped launch a process that could destabilize Britain and rip apart Europe. With Russia's maneuvers in Europe and the number of refugees at a historic high—not to mention the need to promote trade and prevent terrorism—it's hard to see a compelling case to break up. I’m not sure. As with monetary policy or military strategy, some issues seem too complex and too important to decide by a quick show of hands.

Journalist Diane Brady was Canada's national debate champion in 1988.