As a new chapter unfolds in the Syrian crisis, it would be overly optimistic to expect its resolution in the foreseeable future. The 14-year-long civil war and the “slow-motion collapse” of the state have resulted in the deaths of more than 600,000 Syrian citizens, the forcible displacement of around 10 million people, countless human rights violations, an 85% contraction of the economy, and rampant illegal Captagon production. By the time the rebel offensive began, Syria had become both a “failed state” and a “narco-state.”

Against this backdrop, developments since the end of November suggest a deepening crisis that could extend into another decade.

Here are two points, to begin with.

- On the political front, the fabric of Syria’s multi-ethnic society, coupled with sharp religious divides and entrenched tribal structures, offers little promise of stability. Economically, Western experts estimate that rebuilding a “new Syria” could take at least two decades, if not longer.

- While these projections may seem pessimistic, the lessons of Iraq remind us that such assessments reflect cautious realism rather than undue negativity.

For now, let me leave these issues to the test of time and focus on the current situation—dynamic and fraught with pitfalls, including potential optical illusions. I have a few observations that aim to provide a recap of recent developments and assess the stakes for the domestic and international actors preparing for negotiations and confrontations.

The Rebel Offensive: Reliable U.S. sources suggest that the recent rebel offensive may have been initiated by Turkish President Erdoğan. Reportedly, Erdoğan, frustrated with Assad’s repeated refusals to engage in normalization talks, gave his approval for a “limited operation” by HTS (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) and SNS (Syrian National Army) to pressure Damascus into compliance. The aim, according to these sources, was to facilitate the return of millions of Syrian refugees currently in Turkey. However, what began as a limited operation escalated into a massive campaign to topple the Assad regime—a “chaotic success.”

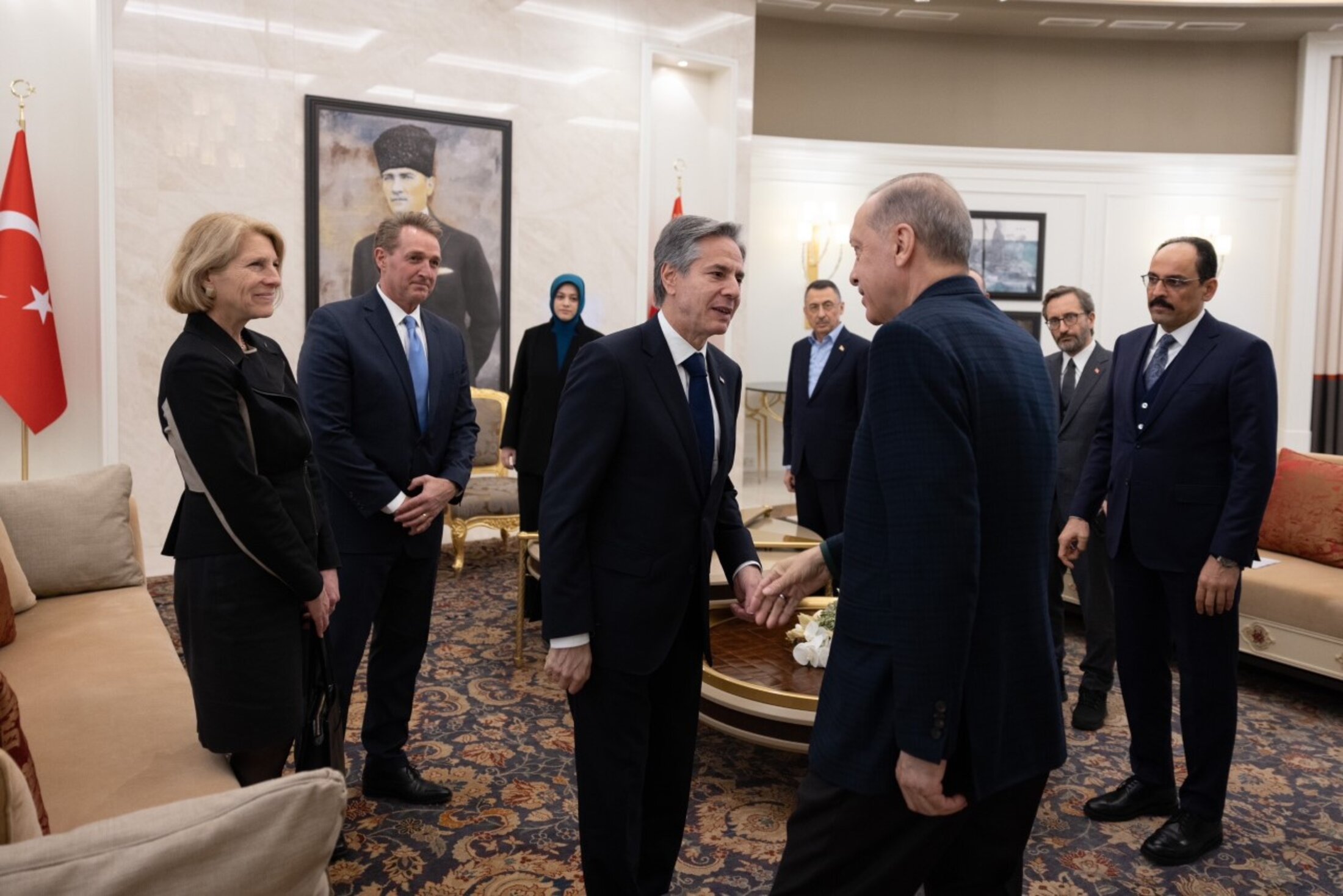

Entrenchment During Interregnum: Another element in Erdoğan’s strategy appears to be positioning for leverage with the incoming U.S. administration in January. This sudden offensive coincided with Israel’s intensified military actions in Gaza and Lebanon, adding another layer of complexity. There seem to little, if any, disagreements between Trump and Israeli PM, Netahyahu, on how to engage in reshaping security map and prospective domination of the region, without Iran’s influence and proxy elements, in the future. Erdoğan on the other hand maintains hopes that his personal rapport with Trump will help secure agreements on refugee repatriation and reconstruction in post-Assad Syria.

Winners and Owners: Since the collapse of the Assad regime, speculation has grown that Turkey, as the main power behind the scenes, is the “winner.” However, “owner” may be a more fitting term. When Aleppo fell on November 30, Turkey seemed as surprised as the rest of the world by the rapid escalation. HTS proved unstoppable by the Syrian Army, prompting urgent crisis management, including a meeting in Ankara between Turkish and Iranian foreign ministers. Meanwhile, Israel seized the opportunity, expanding its control beyond the Golan Heights and dismantling Syria’s military infrastructure. Within this broader context, the Netanyahu government appears to be the true winner, while Turkey is bound to shoulder the responsibilities of ownership of the crisis, it has allegedly triggered beyond its calculations.

A New Regional Triangle: As a result of Israel’s direct and Turkey’s indirect interventions, Iran and Russia has exited the Syrian stage. Astana Process, launched in January with Turkey, Iran and Russia, to find means to end the Syrian conflict is practically over. That triangle is gone. The Israeli government has emerged as a key player, orchestrating a domino effect that is reshaping the Middle East with unpredictable consequences. Hamas and Hezbollah have been severely weakened, Gaza has been devastated, Lebanon has faced large-scale assaults, and Iran’s long-standing regional influence has eroded significantly (except in Iraq). Russia, another vital player, has also seen its leverage collapse, leaving Turkey in a new strategic triangle with the U.S. and Israel—both determined to impose their will, unlike other regional actors such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

The Role of HTS: For some, HTS may appear to be an “Islamist Third Way,” but early signs suggest otherwise. Abu Muhammad al-Jolani’s appointment of Mohammed al-Bashir and key figures from the Islamist Syrian Salvation Government for the new transitional government has raised concerns about further polarization and renewed violence. Jolani’s rhetoric at the Great Umayyad Mosque, emphasizing “victory for Islam” over “victory for Syrians” and setting Jerusalem as a target, offers little cause for optimism.

Turkey vs. the SDF: From the outset of the opposition’s victory, tensions between Turkey and the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces) were inevitable. As HTS advanced on Damascus, Turkish-backed SNS forces pushed the SDF east of the Euphrates River. A U.S.-brokered deal has since established a fragile boundary, with neither side crossing the river. However, Turkey remains adamant about disarming and expelling the YPG, the Kurdish-led armed wing of the SDF, which Ankara views as a terrorist organization linked to the PKK. Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan recently reiterated Turkey’s position, demanding the PKK and YPG leave Syria entirely and lay down their arms. This stance puts Turkey at odds with both the U.S. and Israel, setting the stage for severe confrontations on the field, and tough negotiations after Trump assumes office.

The ISIS Detainee Dilemma: Another contentious issue is the fate of approximately 60,000 ISIS members and their families detained by the SDF in camps and prisons. Turkey has urged Western countries to repatriate their nationals, while suggesting that the remaining detainees should be addressed by Iraq and the new Syrian administration. Fidan has criticized Western reliance on the SDF to guard these detainees, likening it to creating a “Guantanamo” in Syria and warning of the SDF’s potential to use the prisoners as leverage.

In short, we are entering an even more complicated phase in this conflict, which has had a massive effect in global politics, and perception/shift of voters in many countries even far away. Syria’s future remains precarious, with numerous variables complicating the outlook. The interplay of domestic actors, neighboring powers like Turkey and Israel, and the new U.S. administration offers little reason for optimism.

Israel continues by not paying attention to the external world, not even its solid allies. Turkey will probably be the most unpredictable, uncompromising part of the upcoming negotiations, because its foreign policy is profoundly entangled with its crisis-ridden domestic policy, polluted with offensive nationalism and polarisation around identities.

And how Trump will deal with the conflict in the region remains a major question.

With far too many blurred variables, the region risks descending further into disorder.

Agrandissement : Illustration 2