A recent article by my distinguished colleague John Simpson, talking about ending of his optimism about the world in 2015, carried me back a decade ago.

It was in 2014, when I had the privilege of the Shorenstein Fellowship with Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, the early signs for global deterioration had started to be felt. In our weekly, regular meetings with our peers, I noticed, that while the Americans kept their landmark optimism, it was only a very few us, others, delivering remarks of caution and concern.

I had often been talking about the slow motion “self-coup” of Erdoğan, developing since Gezi Park protests, as a harbinger of influence (even an inspiration) for a new generation of autocrats. Canadian Michael Ignatieff, then holding a guest professor’s chair at the department, was airing similar thoughts and expanded them with a more global set of arguments, issuing warnings. I noticed then a lot of shrugs.

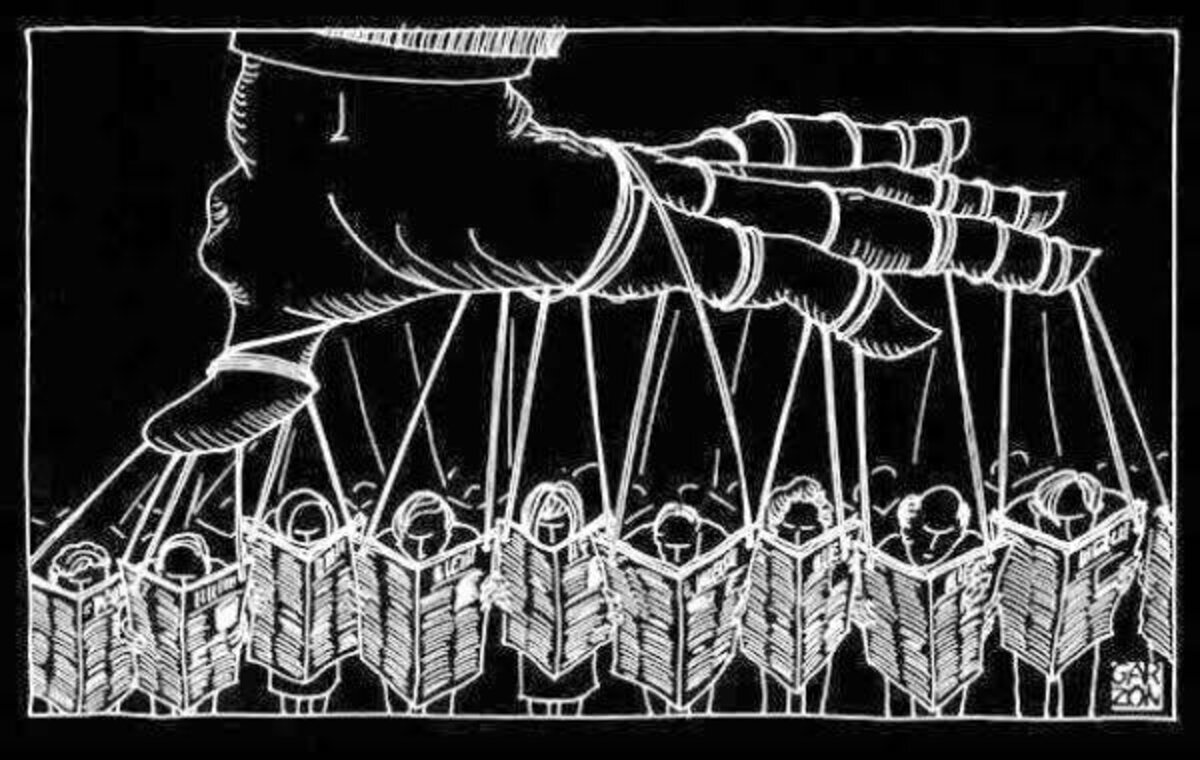

Simpson cites Bill Clinton, as an example of how illusory “the cause and effect equation” between online social media and the shaping of the public opinion, in favour of freedom. Clinton had “famously” claimed, two decades ago, that it would be as hard for governments to control the internet.

"But instead of the technology mastering the autocrats, the autocrats have learned to master the technology”, Simpson writes. “In this new age of autocracy, men like Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Narendra Modi and Viktor Orbán run entire countries according to their own personal political interest, recharged from time to time by carefully manipulated elections… Meanwhile the US, whose opinion used to matter just about everywhere on Earth, suddenly seems as intimidating as a scarecrow in a beet field.”

The colossal change that has been shaking the world, pushing it into commotion, has taken only a decade. If you look at history, you have only one episode in comparison - that between the end of WW1 and the German elections in 1932.

We all know how it ended.

The main difference between now and then is that while the focus was on only one man (and a mentally retarded Weimar president), we are now overwhelmed with his full or half-copies all around us, roaming freely, with the polluting side of the internet (and very soon, AI) at their service.

In reviewing “Autocracy, Inc”, the excellent new book by Anne Applebaum, The Economist reproduces her fundamental findings in what they have in common:

“Whatever their professed ideology, today’s strongmen typically crave little besides power itself and the loot it brings. They share an enemy: checks on power, and the democratic world that espouses them. That common enemy spurs them to collaborate, spinning global networks of mutual support.”

That doesn’t look strange if we look into the interplay between, say, Orban and Xi, or between Aliev and Netanyahu, or between Le Pen and Putin. I am certain we shall see much more daring of acts of such choreography.

But I am these days more focused on Simpson’s metaphor on the U.S.A. as a scarecrow. We would perhaps not come to this connotatiton if the euphoria on the collapse of the Berlin Wall had not overwhelmed the strategic thinking needed on how to maintain a benevolent balancing act in post-Cold War era. History, is a peculiar blend of necessity and coincidence, with the collective mindset of the crowds vis a vis power acting as the engine.

All these three elements required a rock solid perspective into the future of humanity, based on reason. The latter became the victim, and now, we find ourselves in “the Age of Irrationality”, in which a defining battle is between the values of humanism and the forces of evil.

One of the main factors highlighting this is, as the internet is increasingly throttled by the neo-fascist leaders and autocracts, the main social media channels in the so-called “free world” is captured by greedy and ignorant business people. They are all in it solely for the money, uncaring about the consequences of granting space for the enemies of a decent democratic order. They allow feeding of the crowds with big lies and, far worse, large chunks of the crowds are now ripe to swallow them.

“This constant lying is not aimed at making the people believe a lie, but at ensuring that no one believes anything anymore,” Prof Hannah Arendt had explained to us. “A people that can no longer distinguish between truth and lies cannot distinguish between right and wrong. And such a people, deprived of the power to think and judge, is, without knowing and willing it, completely subjected to the rule of lies. With such a people, you can do whatever you want."

And as we now witness in the grand turmoil of the U.S. elections, crowds, once whipped up in state of “ill health”, can be the most difficult to handle.

Commentator Chris Hedges refers to another great thinker of the past century, who barely escaped Gestapo, when he fled to Switzerland in 1938, in an article:

“In Hitler and the Germans, the political philosopher Eric Voegelin dismisses the idea that Hitler — gifted in oratory and political opportunism but poorly educated and vulgar — mesmerized and seduced the German people. The Germans, he writes, supported Hitler and the “grotesque, marginal figures” surrounding him because he embodied the pathologies of a diseased society, one beset by economic collapse and hopelessness. Voegelin defines stupidity as a “loss of reality.” The loss of reality means a “stupid” person cannot “rightly orient his action in the world, in which he lives.” The demagogue expresses the society’s zeitgeist.”

“Nobody’s democracy is safe,”Applebaum says.

The greatest test is only some 100 days away. The result will define lives of all of us, without a doubt.

Agrandissement : Illustration 1