Agrandissement : Illustration 1

For our second post in Mediapart's English club we are happy to present you a translation by Laura Morris of an article written by Armand Hurault and originally published in the edition Paroles Syriennes on the 15th of November 2013. This article described the difficulties of printing newspapers in Syria today.

We, ASML (medialibre.fr) collaborates with the organization SMART to help bring Syrian media projects to fruition. Each week, SMART prints 6,000 copies 11 different newspapers, and distributes them across the majority of the liberated territories.

This article is the first in a series of three on the printing and distribution of these new citizen-led Syrian newspapers. This series is taken from an exclusive interview with Fadi, the lead organizer of the “press project” at SMART, for the Mediapart blog “Paroles Syriennes” (Syrian Stories).

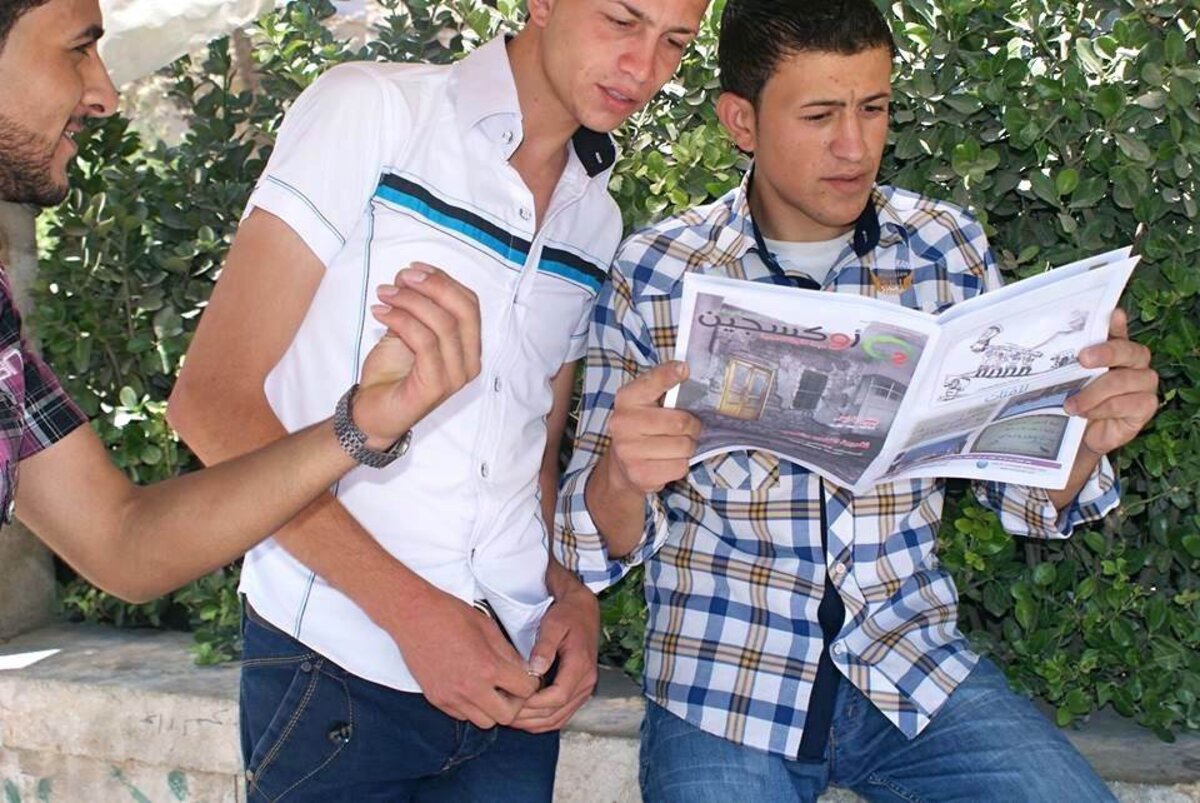

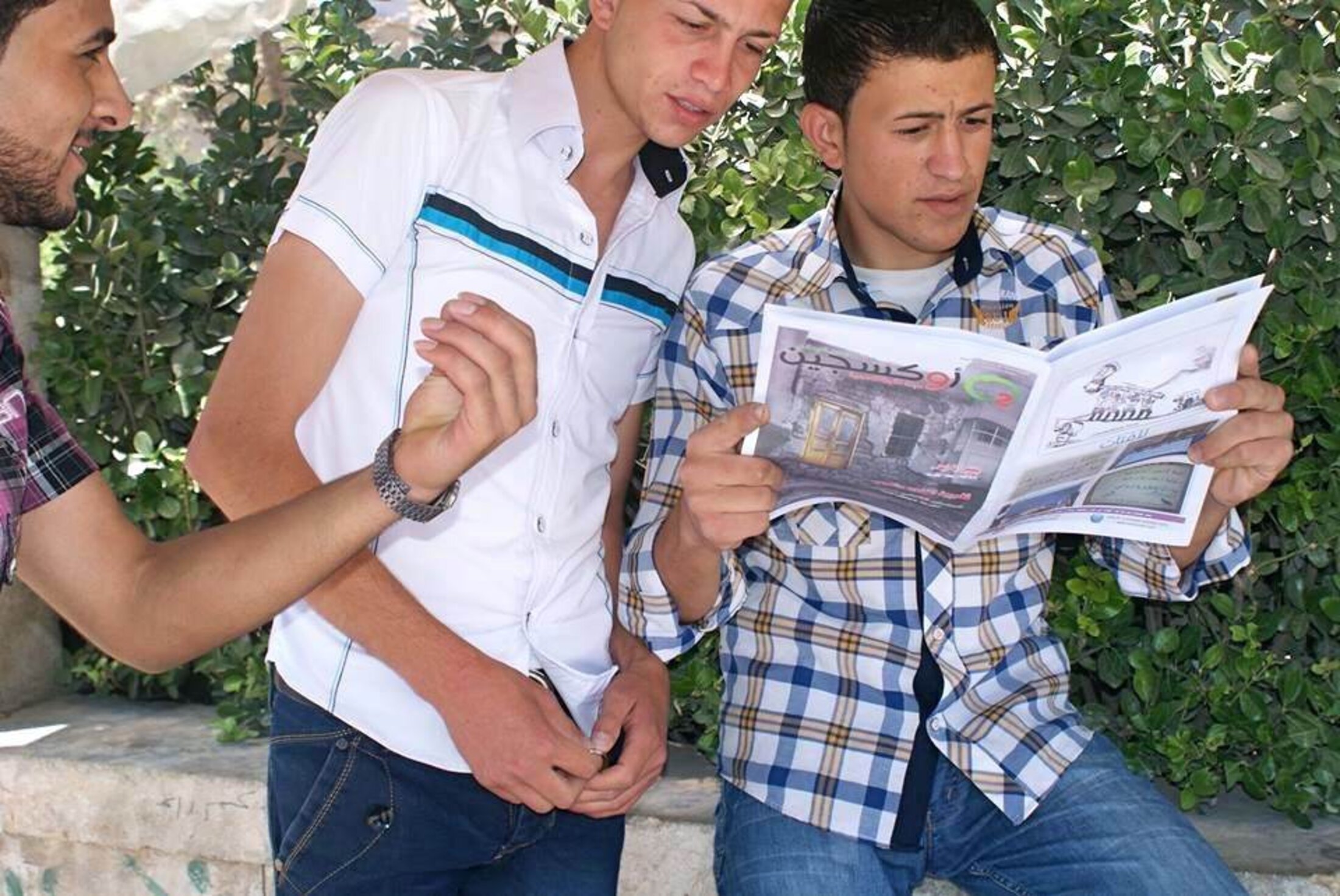

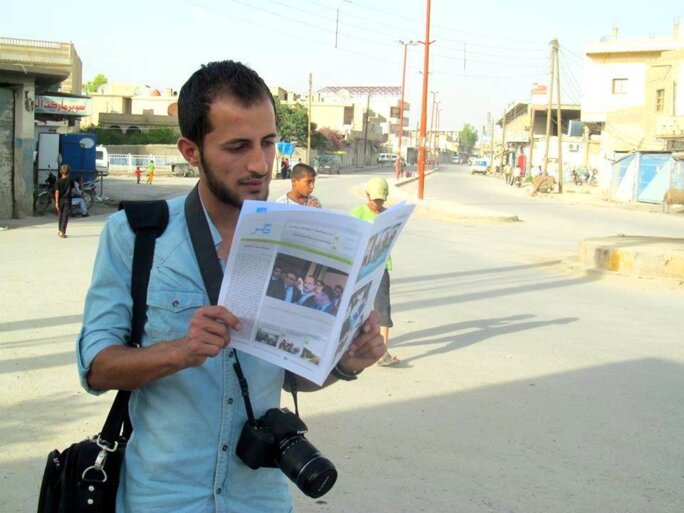

“To hold a Syrian newspaper in my hands that is not filled with inept flattery of the president or his father! This has been my dream for years.”

With these words, Fadi explained what drives his commitment to a free Syrian press.

THE END OF THE PRESS “UNDER ORDERS”

Under the control of the Assad family and its majority Baath party since 1970, Syria’s media has been dictated by government rule for decades. All-encompassing censorship and laws hampering liberty continually stunted the development of a quality press. But the spirit was there, as the dynamic developments of a new press since the first day of the 2011 uprising have shown.

Agrandissement : Illustration 2

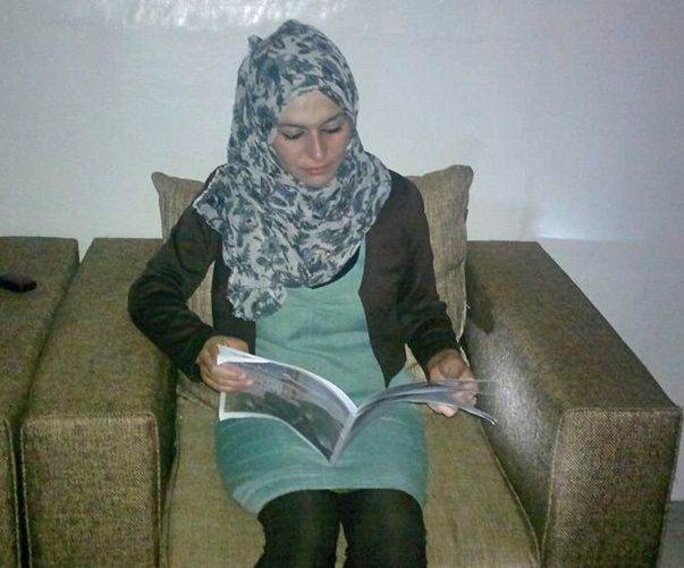

As censorship and subsequent auto-censorship characterized the Assad regime, activists have poured energy into the fight for freedom of expression and access to information since 2011. Starting with Facebook pages, this thirst for information has slowly become structured, and later professionalized, with an overflowing of new media outlets. As found in study undertaken by ASML in the spring of 2013, over 100 journals, magazines, and local news reports have been created since the beginning of the uprising. They range from amateur to professional, some with a local focus, others with a national focus. The journals and magazines cover a wide range of topics: politics, culture, investigative reporting, as well as magazines for children, women, and LGBTQ readers.

The publications share a variety of difficulties: publishing on time despite obstacles, sourcing funds and equipment, and, ultimately, getting their copies to the people.

PRINTING: A MAJOR CHALLENGE

The vast majority of new journals are published online and shared through social media - a popular distribution method due to its simplicity and low cost. But the majority of the Syrian population inside does not have reliable electricity, let alone access to the Internet. Though printing and distributing the hard copies of the journals is a challenge, it is also key to reach the audience, and ultimately, for the future of the country.

Agrandissement : Illustration 3

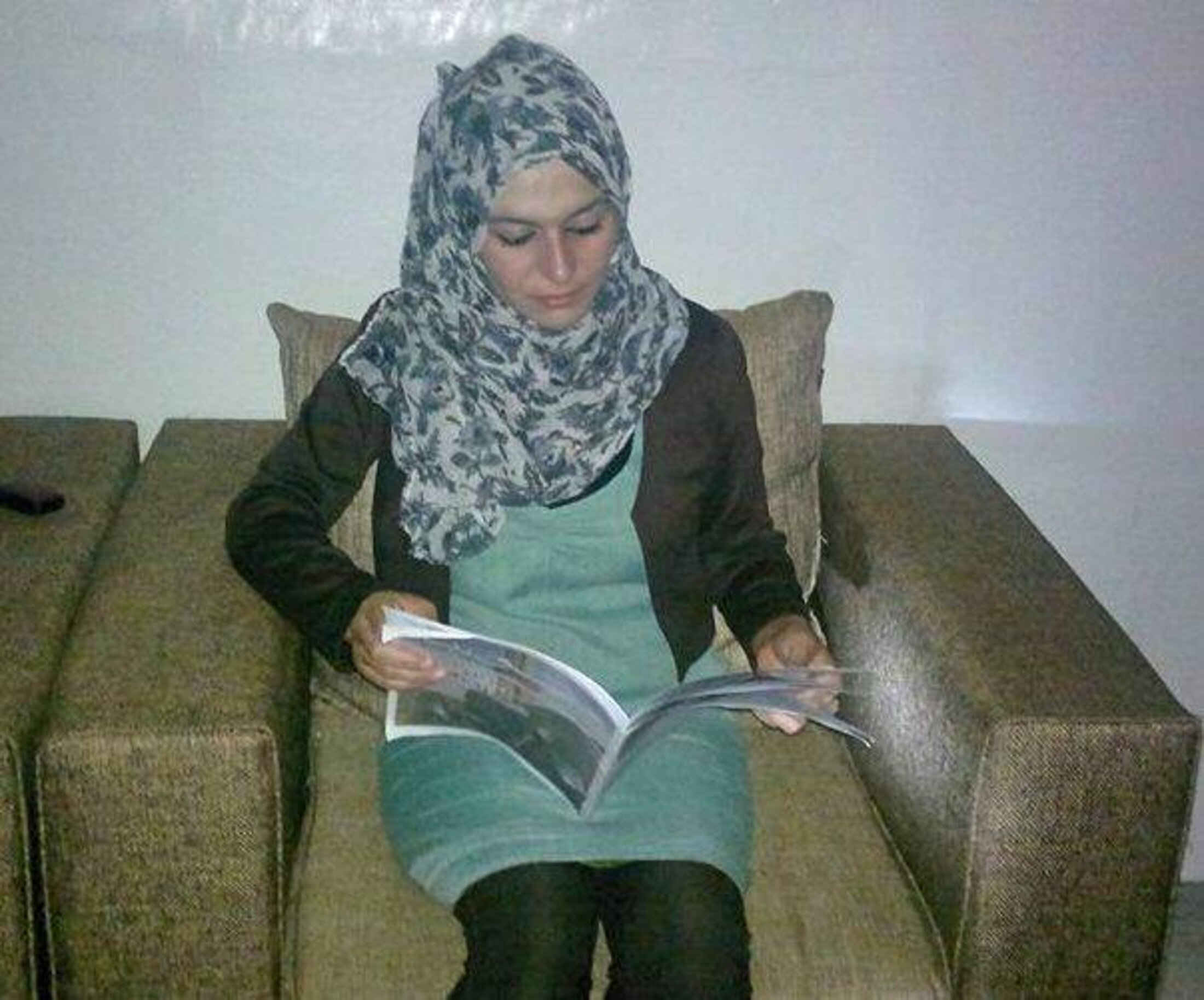

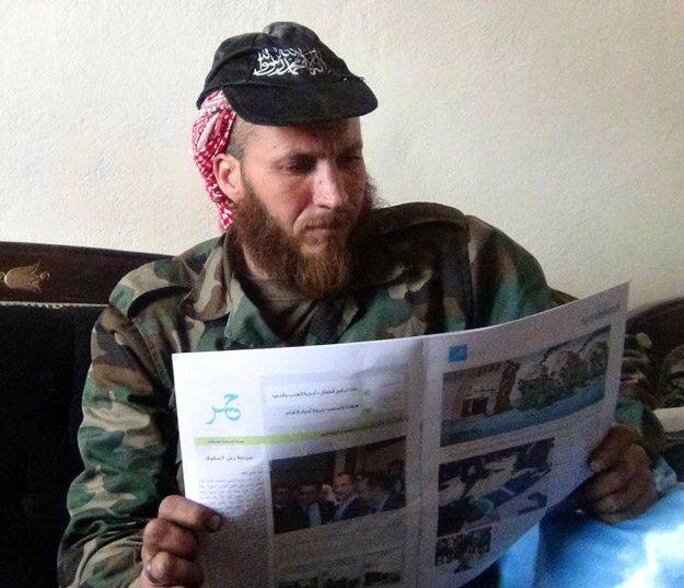

As the crisis worsens and despair grows, the Syrian population is increasingly receptive to the discourse of hatred and intolerance spread by Al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadist groups. Mutual respect, moral and religious tolerance, and a willingness to accept others have been central values to Syrian society for ages, but appear to be crumbling today. For Fadi, these values must be reaffirmed: “Each journal we print is different from the last. They vary in regional origin, focus, political point of view and their relationship with religion. But they are all unified in their basic values of democracy, liberty of expression, non-violence, and moral and religious values.” Fadi continued, “We are sure that this is the best way to fight against the development any sympathies to jihadist thinking. Media is key to ensure that Baathist thoughts are not replaced by sectarian, intolerant, war-driven ideas”

Agrandissement : Illustration 4

But this is easier said than done. Printing is expensive, and none of the journals have the resources to print on a large scale. To reduce costs, they share resources. This problem of resource availability was at the origin of SMART’s involvement in the project, supporting the journals by taking on the responsibilities of printing and distribution, free of charge.

POWER, INK, PAPER, BOMBS: ENDLESS DIFFICULTIES

The obstacles are numerous. Firstly, there are frequent electricity shutoffs. “In the north, where the print center is located, there is perhaps 30 minutes per day,” explained Fadi. “We can’t count on it. We have had to find ways to get around it.” He explained: “We have installed generators, as well as solar panels and small wind turbines to charge batteries during the day that we can then use at night. We also keep a reserve of gasoline for the generators. To be able to print continuously requires complete independence from the public sources of energy.”

Agrandissement : Illustration 5

The second difficulty is to get the digital versions of the newspapers to the print center. For security reasons, the majority of editors work outside of Syria. However, the print center is located inside, where there is no available Internet connection. “Each edition is sent to the center by satellite connection. We have equipped the center with a satellite modem, allowing us to get around the national internet [blackout].”

Agrandissement : Illustration 6

Not surprisingly, another difficulty is sourcing ink and paper. For this problem there is no permanent solution. “When we began the project in May we scoured the liberated zones for ink and paper. It was rare, but we could find some. And we bought everything we found.” Fadi smiled, “the other side of the coin is that we unfortunately have to go into the regions controlled by the regime to find more.” Fadi’s casual manner belied the dangers he was speaking about; journalists and “media activists” are prime targets for the regime, and the risks they take on in this work are extensive.

Agrandissement : Illustration 7

Fadi noted that these daily risks are not unique to the project but touch the entire population. What the press commonly calls “liberated areas” are liberated in name only. When the regular army has left an area, they leave behind an ongoing state of war with regular bombings. The city in which SMART prints is located in a “liberated” zone, approximately 15 km from an army air base. Every day, missiles and rockets fall on the city, along with daily visits from MIG fighter planes and machine-gunning helicopters dropping barrels of dynamite. “To protect the team, maintain the continuity of printing work, and keep to the distribution schedule, we have taken all kinds of measures.” Fadi enumerated: “firstly, our premises are underground. What’s more, the military base is to the west of our city, so we make sure to work only in the rooms located to the east. As the bombs are more frequent during the day, our team works only at night, leaving the city in the morning.” Not surprisingly, even with these precautions they experience danger and occasional delays in printing or delivery. “The objective is to reduce the risks to a minimum,” explained Fadi, “of course, we cannot control everything. The country is at war, after all.” Nonetheless, the entire team seems persuaded that the end goal is worth the risk.

Fadi concluded, “Everyone on the team is a volunteer. They are compensated but they don’t work for money. They believe in what they do. They fight for a better future. They do not want Syria to become a dictatorship again, and they do not want a jihadi caliphate.”

And if this third way were to pass by the press?

Article written by Armand Hurault

Translated by Laura Morris

Agrandissement : Illustration 8