Like every year on the anniversary of its creation, on March 16th 2008, Mediapart makes public all its operational figures, accounts and results. They can be found here, and in the brochure below

Le carnet des 14 ans de Mediapart 2008-2022It can never be overstated just how unique this exercise in transparency is in the French media landscape. While most of the independent media that make up the Syndicat de la presse indépendante d’information en ligne (Spiil) – the association of independent online news providers of which Mediapart is a co-founder and member – oblige themselves to do so, the still dominant traditional media choose not to, citing the “business confidentiality” of their financial results in order to mask the amount of public subsidies they receive, and the private funds they accept from digital platforms.

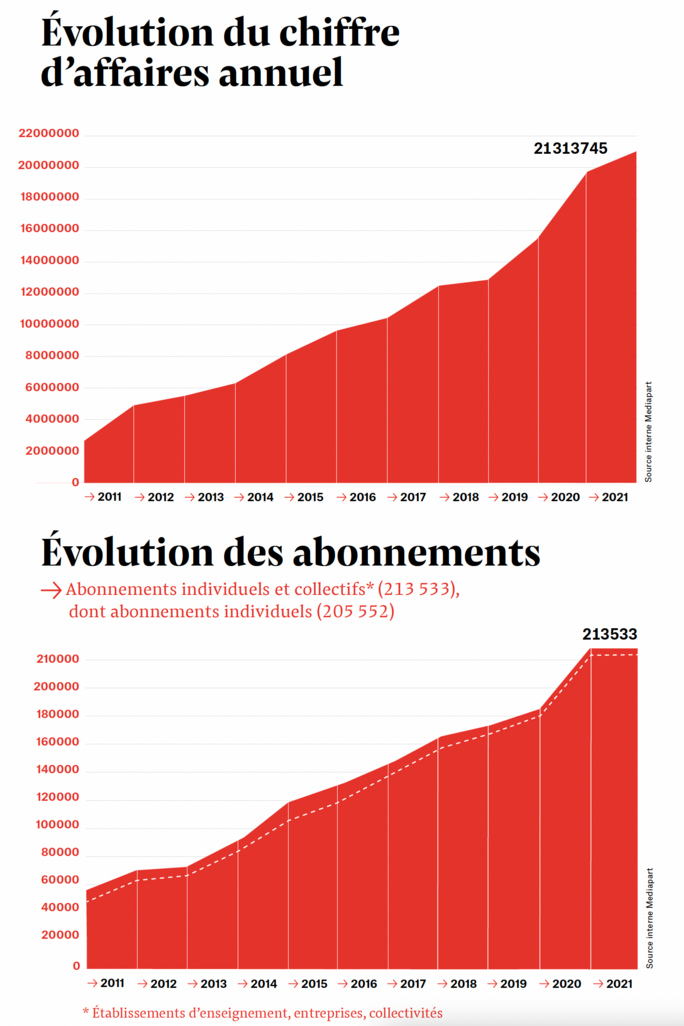

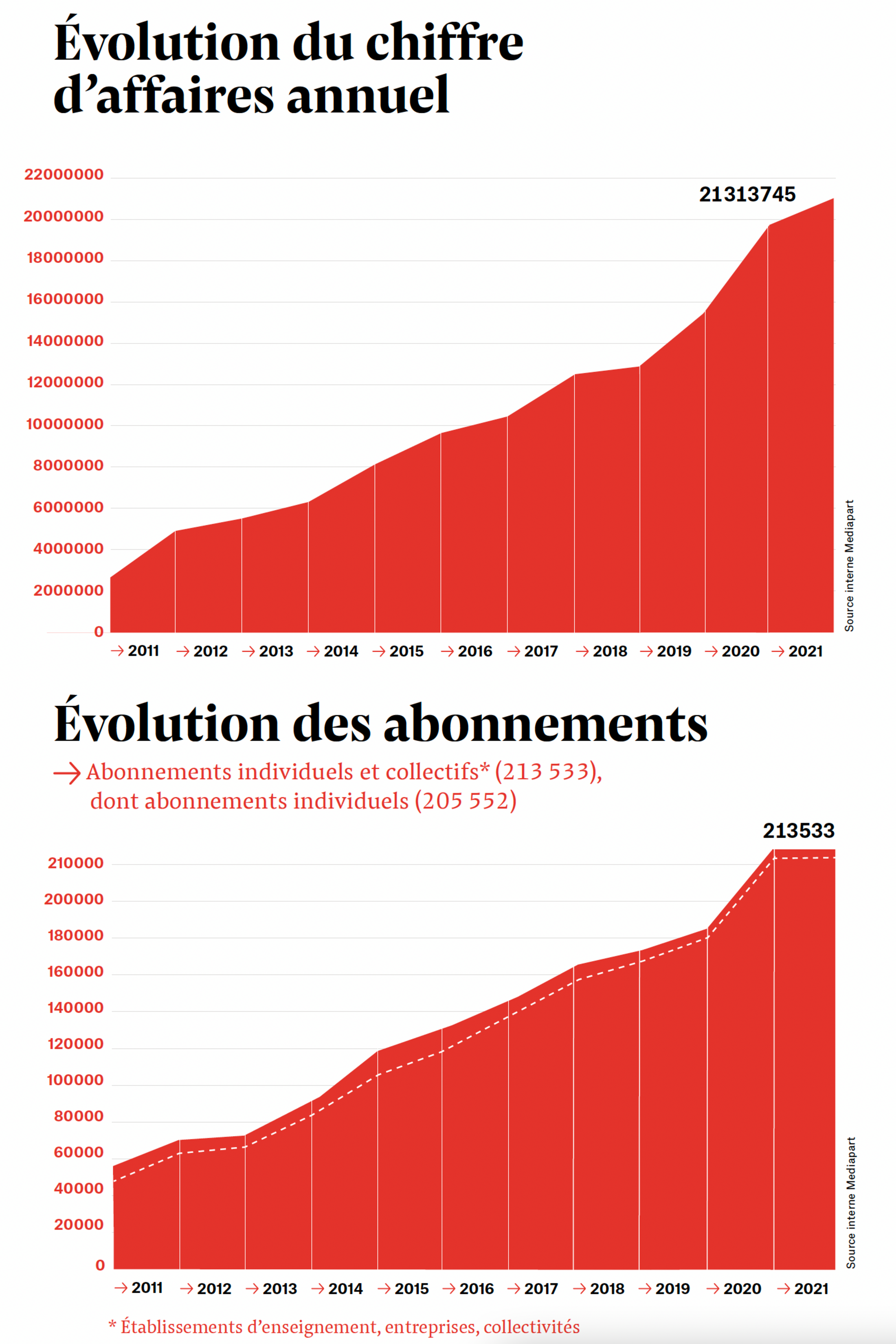

As it now enters its 15th year of existence, Mediapart’s latest results confirm the solidity of its economic model which is founded uniquely on the loyalty of its readers, whose subscriptions account for 98% of its income. After an exceptional growth in 2020, when we passed above the landmark figure of 200,000 subscribers far earlier than we had envisaged, the year 2021 was one of continuity, with a total of 213,533 subscribers (individual and collective subscriptions).

The two graphs below show the evolution of our annual turnover, in euros (top), and the yearly evolution of subscriber numbers (bottom):

Agrandissement : Illustration 2

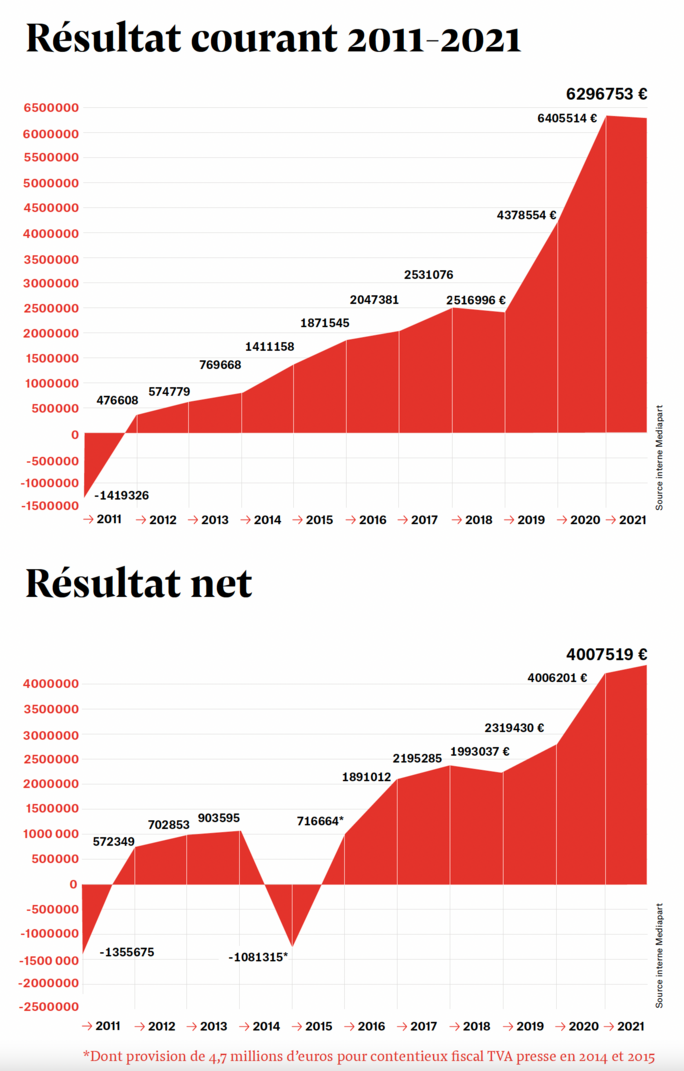

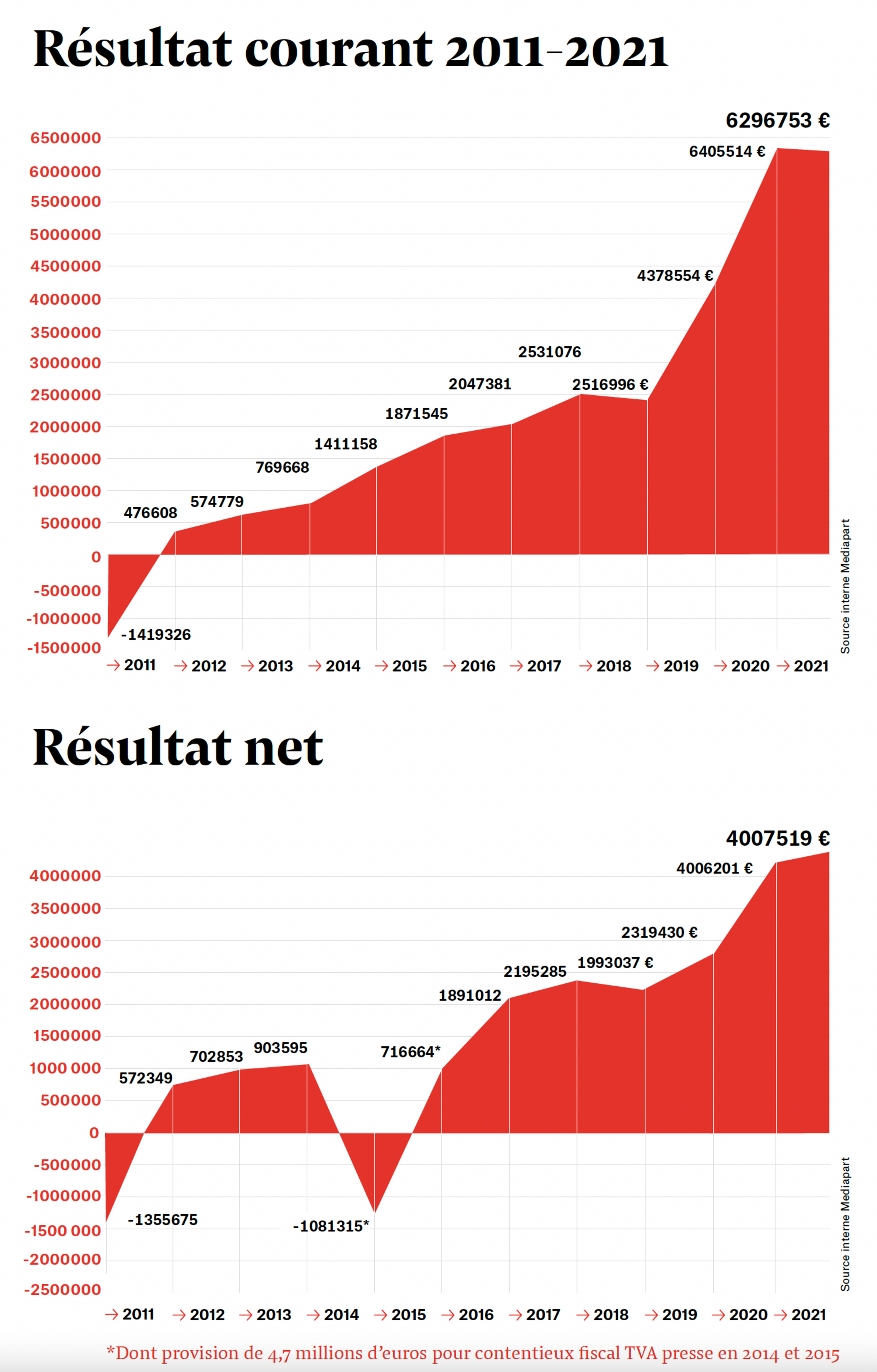

Beyond this strong stability, the principal observation is the structurally viable character of Mediapart’s finances. With a slight increase in turnover (21.3 million euros in 2021 compared to 20.4 million euros in 2020), Mediapart achieved current earnings, before tax, of almost 6.3 million euros (more precisely, 6,296,753 euros, representing 30% of turnover) and earnings after tax and staff participation payments of 4 million euros (more precisely, 4,007,519 euros, representing 19% of turnover).

The two graphs below show the evolution of our current earnings, in euros from 2011-2021 (top), and the evolution over the same period of net earnings (bottom):

Agrandissement : Illustration 3

Far from being at the expense of Mediapart’s development, this remarkable profitability was achieved to a backdrop of numerous developments during 2021. Notably among these were the introduction of a new mobile app; a new layout for the website; increased video productions for our daily current affairs programme ‘À l’air libre’; the creation of new podcasts; a publishing partnership with news cartoon magazine La Revue dessinée; investment in the making of the documentary Media Crash, released in cinemas around France; growth in staff numbers, which rose from 118 in 2020 to reach 131 in 2021 and, finally, the moving of our headquarters in Paris into larger offices in order to adequately house the expansion of Mediapart.

Mediapart’s profitability was obtained without recourse to any of the artifice, expedients and pretences employed in a French media landscape dominated by a handful of billionaires who promote their private interests, seeking influence and protection, all to the detriment of what should be the mission of journalism: namely, to serve the public interest. That is the best defence of our independence which, since 2019, is guaranteed by the Fonds pour une presse libre (FPL) – see the presentation in English here – which is a not-for-profit structure dedicated to serving the freedom and plurality of news organisations, and which has become the sole, unique owner of Mediapart, via the ‘Société pour la protection de l’indépendance de Mediapart (SPIM)’.

Combatting the concentration of media ownership

Reshaping the ecosystem of news reporting

“Any moral reform of the press will be in vain if it is not accompanied by appropriate political measures to guarantee a real independence of newspapers with regard to capital.” Those words by Albert Camus were published in Combat in the summer of 1944, and are today as pertinent as ever. Mediapart’s success can in no way hide the dilapidated state of the French media landscape, where a concentration of economic interests joins in a downward ideological spiral that promotes anti-democratic opinions and smothers information of public interest. It was Camus, once again, who had predicted the danger. “Everything which degrades culture shortens the paths that lead to servitude,” he wrote. “A society which allows itself to be distracted by a disgraced press […] heads for slavery, despite the protests of those very ones who contribute to its decline.”

The inventory is there to see: never in our history of democracy has the communication sector known such a takeover of news reporting by outside, private interests. In France, 91% of national dailies, published online and on paper, belong to a handful of billionaires, while 44% of TV broadcasting is controlled by three of them (Martin Bouygues, Vincent Bolloré, Patrick Drahi). With the takeover of the Hachette publishing group by Vivendi (Bolloré), and the merging of TV channels TF1 (Bouygues) and M6, the concentration of ownership is further accentuated.

Both horizontal with regard the numbers of media they own, and vertical with regard to their diverse economic activities, this concentration of proprietors represents a flagrant abuse of dominant positions, generalised conflicts of interest, and the pressure of advertising interests on editorial teams. Until now, this concentration has met with no resistance from the French authorities – which have even accompanied it. The transformation of broadcast frequencies into channels of hate propaganda has not been penalized by the broadcasting regulatory body. The majority of public aide provided to the press falls into the purse of media oligarchs, to the point where those newspapers owned by France’s wealthiest individual, Bernard Arnault, the chairman and CEO of luxury goods group LVMH, are given almost one quarter of it.

Added to this connivance by the state are the opaque agreements made by these media oligarchs with digital platforms, such as Google or Facebook, which, by subsidising the former, obtain allies to maintain their positions of monopoly. The issue of the “related rights” due to the media by the so-called “Big Tech” corporations exposed this collusion, which a French parliamentary commission found disturbing. In opposition to the course these media have taken in order to reinforce their dominant position, Mediapart, following the initiative of its professional association, the Spiil, is involved in a collective and cooperative mobilisation of publishers.

Because, far from creating so-called media “champions” as these billionaire proprietors pretend, this concentration weakens democracy by destroying the value of news reporting, along with its originality, its diversity and its authenticity, to the profit of clashes, of propaganda, and the rise of a climate of hate. Its economic model is centred on audience figures, indiscriminate and anonymous crowds, to the detriment of a patient construction of democratic dialogue between sections of the public concerned with gaining access to facts and truths. That is how, far from promoting quality amid the digital revolution, it follows the worst downward slope, transforming entertainment into diversion.

Contrary to that, the universe of independent media to which Mediapart belongs stands out as a space of innovation, to the point of having prompted the principal reforms of the French media ecosystem over these past 15 years: the creation of a statute of the online press, the economic model of paid-for access, technology neutrality, equality of VAT rates for the digital and printed press, transparency regarding the allocation of public aid, new audio-visual formats, a participative relationship with their audiences, non-profit endowment funds, etc.

It is of no surprise that these independent media also promote, along with professional unions and journalist staff associations, democratic requirements as counterweights to the concentration of media ownership. These include rights for editorial teams that guarantee their independence, limits that prevent the concentration of horizontal ownership, barriers against the domination of advertising, the banning of the takeover of news organisations by industrial interests, and the recognition of influence peddling.

As a little fish swimming beside big sharks, Mediapart is intent on participating in this combat to clean up the media ocean.

> The ‘Stop Bolloré’ collective is holding a public meeting in Paris on Friday, March 18th, entitled “The concentration of media ownership kills democracy”, between 4pm and 10pm at the Salle Olympe de Gouge, 15 rue Merlin, in the 11th arrondissement.