Translation : Cydney Puckett and Antoine Bernuchon-Verrier

French version : https://blogs.mediapart.fr/hippolyte-varlin/blog/201220/de-son-pays-fleuve-la-gambie-abdou-manjang-nous-confie-l-ame-et-ses-refrains

Abdou Manjang is one of those rare beings you meet once in a lifetime, dividing time into a before and an after. Spotted by photographer Clément Martz in February 2017, Manjang stood out.

https://medium.com/@clementmartz/abdou-s-life-in-the-new-gambia-e4a0eff1a43d

His unquenchable thirst for knowledge and human connection made him remarkable. Dreaming of a distant elsewhere above all else, Manjang overwhelms one’s emotions and tugs at the heartstrings. Martz is still impressed by him today: the young thirty-something surrounded by children, but also by friends, neighbors, all his brothers and sisters in misfortune who call on him for help despite the fact that he has nothing. Manjang sleeps on a mattress on the ground in his clay house, the battered floor serving as his bed frame. He dreams of traveling. A broken record of wanderlust plays in his head all night. Each morning these nocturnal escapes are wiped away by his reality; each year, the rain dissolves his family’s clay home and it must be replaced by cinderblocks. But the project can take years, never-ending years….

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

Here, alongside his beloved only sister, something becomes blatantly obvious: their vivid, brightly colored clothes, those worn only for special events and always handled with the most careful hands, read ‘dignity’; a profound elegance that poverty, trauma, nor lack of perspective can impede. In the background is Jaimundaw, the neighbor. No one in this village is forgotten. Perhaps you’ve noticed it as an unsettling detail: Manjang’s gaze, which friends describe as both fragile and piercing at the same time, but wholly beautiful.

Agrandissement : Illustration 2

Manjang’s eyes stop where austerity devours childhood.

His country? Banks of a river, encircled by neighboring Senegal, a country seventeen times larger than his own; a reverse peninsula, meeting the Atlantic on one side and the Senegalese border on the other three. The river overlooks the ocean, as it did in the past, when the island of Banjul was first used to control the region’s slave trade. It’s on this island one can find the capitol of the smallest country in continental Africa, a country where nearly 2 million people call home. Despite being small in both population and geographic size, The Gambia is one of the main origin points for those found by SOS Mediterranée, an organization working to find and save those in distress on the world’s most deadly migration route. Among those who have disappeared, Manjang’s brother, a helpless wanderer swallowed by the seas in 2006. His name was Amadou Manjang, and his journey was motivated by the need to provide for the family after his father died of cancer. He was both a brother and a son, gone and without a proper grave, but forever memorialized in the hearts of his family members, while all that remains of Amadou is an image on a mobile phone. Manjang suffers in silence, and will only mention his late brother after expressing all of his affection for his country. “About my country, I love the love that runs through it, the solidarity that expresses itself faithfully, the interest in culture, the support that unfolds in times of mourning…” Then he adds: “We benefit from sunshine favorable to oranges, mangos, bananas, and other plants.” Manjang is a modest and enthusiastic young man, and his soul remains wounded by the traumatic losses of his brother, uncle Magidou Njie, and best friend Lamin Bah. All three lost while in search of a better life. Manjang can picture Bah, an unforgettable spirit, clinging to his younger brother, Sulayman Suso, with exhausted arms in their final moments as briny water fills their young lungs and the sea envelops them. A final voyage financed by the sale of their mother’s land….

And Manjang knows he must leave.

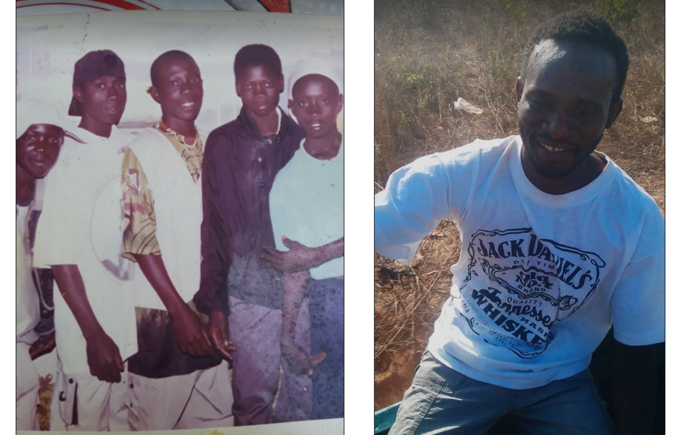

Agrandissement : Illustration 3

Amadou Manjang, first from the right, during his joyful adolescence; Lamin Bah, in his homeland, before departing on a journey from which he would never return. A brother and a best friend, what life sometimes offers...

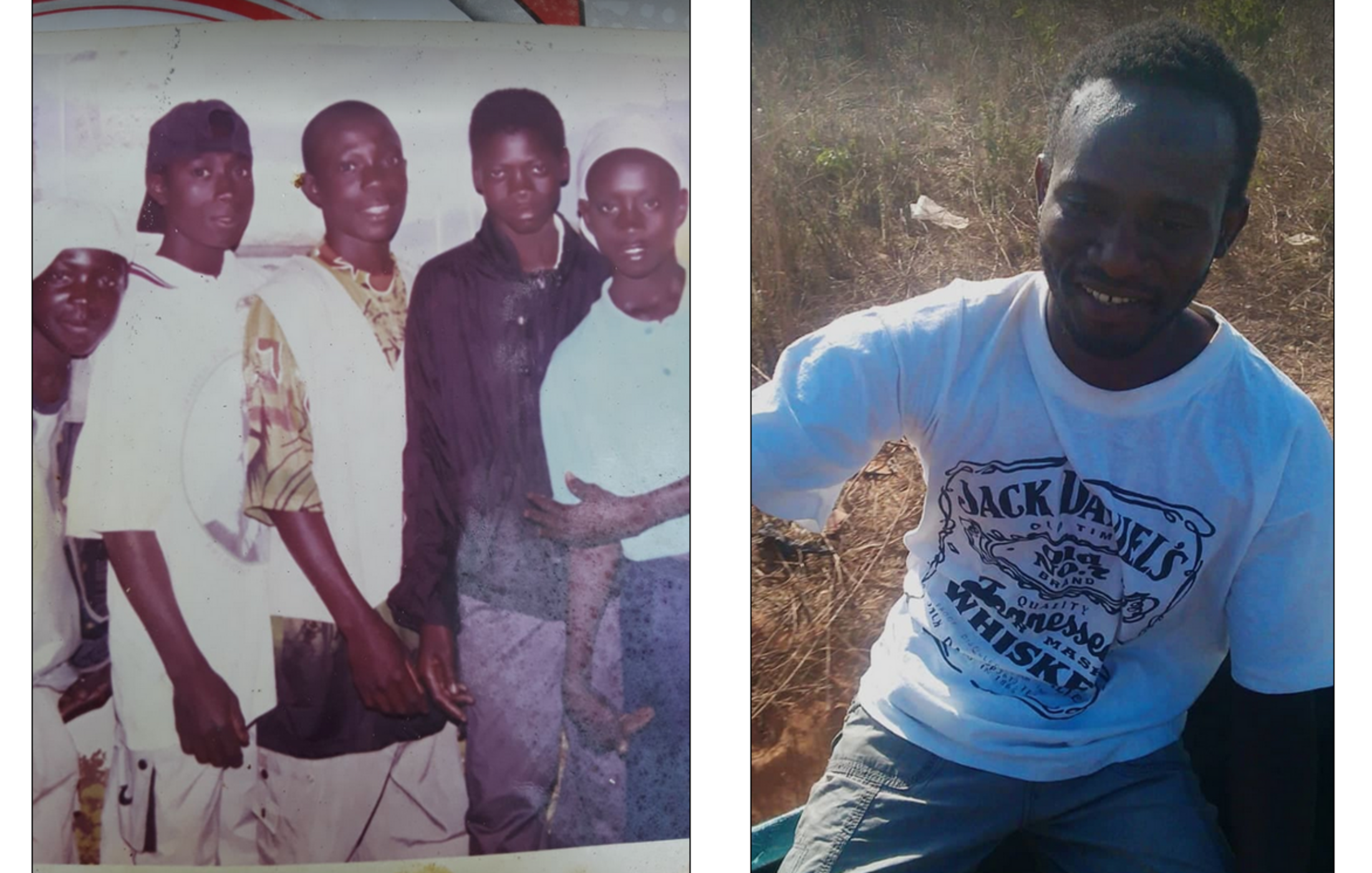

Agrandissement : Illustration 4

This is how one would meet him, at the corner of a street or avenue in Europe or in North America, one of the "elsewheres" he aches to discover. He understands the cultural norms, the language, as both are colonial inheritances. The young man loves to express himself in English, so much so that he will think in the language too. A shipping container of clothes arrives in the port of Banjul regularly, sent by enterprising expatriates working to globalize not only their designs and styles, but their Gambian sense of dignity as well.

We asked Manjang to collect the stories of people in his village and share them with us. That was not easy for everyone. Oftentimes, digging up the past reopens old wounds usually concealed by composure. Amadou’s departure for a hazy Eldorado is a wound that will never heal. His 44-year-old mother, Sunkary Njie, remembers his answer to her final warning and evocation of his missing uncle: “Mom, I’ll be back with money and I’ll help you. I’ll help you to get out of this nightmare.” But the nightmare continues. “I’m a gardener” she confides, “and I have to walk long distances to reach my workplace each day. Selling vegetables and fruits isn’t enough. I have another job at the beach where I carry people’s stuff, and they pay me for that. I’ve been doing this for several years now, waiting for the harvest season. We have no beds, no decent food, no drinking water. No mother on earth deserves this curse.”

Agrandissement : Illustration 5

Sunkary Njie, standing before a flickering flame, her brightly colored clothes struggling to animate an expression on the withered face her son will never see again. “Poverty is an incurable disease” she tells to her Abdou, who refuses to stop trying.

Manjang’s search for stories would not be complete without a visit to a village elder. To what extent does climate change impact Gambia? Pa Jammeh is happy to answer, but not without reminding him of their culture’s conventions: a virtuous life, respect for the elders, unconditional solidarity, the imperative of knowledge, and a loving home that can warm the coldest of souls. Then comes his answer on deforestation, which is slow and sure and a consequence of producing charcoal, and the deforestation is only exacerbated by the erosion caused by ever more powerful rains, floods, and winds, which compromises the forest’s ability to regenerate. He recalls these same forests once served as a barrier and also as the pharmacopoeia of the people living in them. Poverty is an infernal circle… And under a shared sky, greenhouse gases have no use for borders or visas.

Agrandissement : Illustration 6

The venerable Jammeh remarks: “ Our parents taught us to respect each other and to help each other just as much.”

Unquestionably, Manjang’s pride is deeply reflected within Jammeh’s words. He works in a nearby school for $50 per month, just enough to buy rice for the seven members of his household and maybe a candle for light when the sun starts setting early. Manjang finds his work gratifying and he feels privileged to do it: “I feel a profound happiness working here with the children because I know they are the leaders of tomorrow.” This feeling is amplified each year during an annual celebration that brings together several schools from the region: “We aim to offer them dignity and to make them understand that each of them has a place in our society,” as well as share with them, “human values such as solidarity and brotherhood,” concepts solidly rooted in the hearts and minds of those working at the school.

Agrandissement : Illustration 7

Manjang’s place of work for the last two years: Sheikh Hatab Memorial Nursery School.

Agrandissement : Illustration 8

Luckily, friendship and fun are free.

Agrandissement : Illustration 9

The start of the school year comes with a sanitary protocol which shadows children's daily activities. But the snack break is always savored as much ...

Manjang remembers his father putting the highest emphasis on the importance of school: dressing smartly, keeping school supplies organized, but… no meals. “It became clear to me very quickly that it was useless to ask my parents for something to take for lunch. The shame they felt for not being able to feed me was too great. When I was 9, I went to school on an empty stomach.” Manjang did find solidarity in the charity Le Bonheur des Orphelins after his father died and he had to leave school to work finding wood fuel. Thanks to the organization, Manjang was able to return to school until the school building collapsed, which sent him back to work. This time, however, it was to finance his opportunity to take his final exams in a private school. And all along the way, his close companion, hunger, gnawed away at him. Manjang sees his interest in working with children as a legacy from his mother, for whom he has infinite respect. As a child, he saw her provide breast milk to infants in several neighboring villages. Solidarity is the very cornerstone of Manjang’s family and his people.

Yet the yearning to escape lingers still. Manjang spent seven years expatriated in Freetown, the capitol of Sierra Leone, working in a neighborhood daycare center and sending as much money to his family in the Gambia as he could. This money, though only enough to buy rice, candles, and few precious extras, was a lifeline allowing those Manjang left behind to survive. Now back in his home village, he is working in a school with young children, a precarious situation thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic (his school was closed for several months). From then on, Manjang was consumed again by the temptation to leave, buttonholed by the great success stories of some who had made the leap. But for him, the blows keep coming. “The woman I love left me because of my poverty.” A life, love, impulses, all undermined without mercy. “Poverty is an incurable disease….”

Agrandissement : Illustration 10

Rebuilt year after year with bricks made from the garden’s soil, the home of the large Manjang family, a mother and her six children.

Agrandissement : Illustration 11

October’s rain wreaked havoc on the family’s house. Inevitable and costly, a roofer works to repair the damage, supervised by the family’s mango tree.

Agrandissement : Illustration 12

One of Manjang’s brothers sleeping on a dirty mattress directly on the floor. Dreams are his best weapon to ease the harsh reality, but only until sunrise interrupts.

But he always manages to snap out of it after hearing the stories of the unsuccessful. Libya and the Mediterranean Sea are almost inescapable parts of the journey to Europe, known as the “Libyan Hell” and the “Blue Cemetery” for good reason. Marie Rajablat, along with SOS Méditerranée, has denounced the slave trade that is largely accepted by the Libyan government. Preying on the makeshift boats that set sail for Europe, Libyan slave traders kidnap, hold for ransom, torture, rape, and slaughter the broken men and women, packed like sardines in inadequate dinghies, which have the misfortune of being caught in Libyan waters. The migrants are usually captured by militias or the “border guards” (trigger-happy Libyans financed by the European Union), but occasionally found by rescuers (though increasingly rare and criminalized). The last possibility, a risk ever-present in the minds of those headed to Europe, is sinking; adding to the 20,000 recorded deaths since 2014. Wanting to be wise, Manjang chooses a different outcome in The Gambia: “I aspire to see international associations give us more means to limit this illegal, mass migration further destroying The Gambia. It is my hope that these few testimonies will allow people to open their eyes and seriously consider protecting the migrants and improving their living conditions. I hope to see my Africa happy one day.” Wisdom is salvation for a man who hesitates between two dreadful options, but it doesn’t stop reality from catching up to him: the unsound and poorly-equipped house, the lack of clean drinking water due to unsanitary wells, the daily question of food, the exhaustion that devours the nights and withers the days. These stories, full of rigor and hope and despair oblige us to do something.

47 year-old Omar Camara does not want to dissuade Manjang from migrating; on the contrary: “I encouraged my own son to leave the country in search of a better life. Not without frustrations, of course. Most of my friends do the very same thing. We want to give our children a chance. We are not afraid of death.”

Agrandissement : Illustration 13

Omar Camara: “We work to eat. I have to work several jobs to protect my family from famine: I make bicycles, transport goods with my cart, and sell the wood I collected in the bush.”

Then, Jariyatou Sawanneh drives the point home: “ Freedom is a synonym for death here.” The children are alone in their little house, waiting for their father to return from his work in Banjul. Sawanneh spends her days selling fish at the market in Gunjur. Then night comes, providing a chance to have a meal together as a family, but without electricity. And then there’s school, a luxury, one that the father never got to enjoy: “My husband, he never had the opportunity to attend classes. I don’t want this to happen to my kids” Jariyatou concludes. As for the night, dark though it may be, it cannot dissolve the father’s broken promise to support those who stay. “Our misery is a never-ending circle with no destination.”

Agrandissement : Illustration 14

Jariyatou Sawanneh: “In Africa, women work like dogs without enjoying the least bit of freedom.”

A fellow sister in suffering, is Bintou Bajinka, 35 years old. Her story further describes the impasse. A widow, a forgotten step-child, and a gardener in perpetual search of rice, dried fish, and candles for her seven children, whom she hopes will be sheltered in a house, even if every drop of rain makes it one step closer to collapsing. One day her eldest child asked her: “Mom, do you seriously think we can stay here and do nothing?” “To go where?” Bajinka responds to her son, who searches for a way to change things, to no avail. As if a question were a means of escape, an exchange creating the illusion of a controlled existence. “Sometimes I wonder why the rich don’t turn to the poor. We don’t want to see our youth run away. Death is part of this journey. I know it is. Poverty is deadly. “

Agrandissement : Illustration 15

Bintou Bajinka: “Leaving to die, that’s how I see it.”

Manjang faces the critical gaze of Ebrima Jatta, whose acute awareness echoes that of Pa Jammeh’s concerns. In an attempt to combat deforestation, Jatta plants new trees in the place of the ones he had cut down, but only when he is not busy digging wells or building the foundation of houses. He states that deforestation is gnawing away at the country, helped by the pandemic, which has extinguished the few existing efforts to combat climate change. It’s no mystery why people are literally dying to flee a country where “70% of the population is out of work,” a magnificent country which could be “an oasis” but is currently nothing more than “black misery.” Europe is seen by its people as a continent where children “don’t go to bed hungry”, a land where “people don’t work to the detriment of their health.” Europe is an obligatory passage before the return home, as many Gambians have done. Jatta must also be aware that neoliberal globalization, which locks borders for humans and applies itself to suck the poor dry in order to douse the rich, undermines the most entrenched solidarities, including in Europe. International solidarity? The world is being mapped, relentlessly, even today: Europeans? They are part of the 15% of the world population that owns 62% of the world’s wealth. And Africans? Part of the remaining 85% with 38% of the world’s wealth, according to geographer Nicolas Lambert. Manjang is increasingly sensitive to this as he thinks about the future generations of Gambians.

Agrandissement : Illustration 16

Ebrima Jatta: “The coronavirus slowed down what was already stagnant.”

Manjang will never abandon his desire to improve his community. He introduced us to the Balakafoo project, meaning ‘having sympathy for each other’ in Mandinka. Starting in 2006, each member contributes one euro per month, filling a community fund. “We withdraw a certain amount from the common fund to help those in distress.” It is like a bank of solidarity. For instance, they help when someone needs money to build a fence, buy land, or install decent lighting. When a ceremony or celebration is organized, Balakafoo contributes in order to preserve cultural traditions and reinforce a feeling of community. They always act in a complementary fashion and therefore focus on how to rebuild what has been destroyed.

Agrandissement : Illustration 17

A great team. Pictured here, the members of Balakafoo at a meeting in 2020. Manjang thought it important to give the names of everyone involved in the Balakafoo project: Saikou Jammeh, Alige Jatta, Ebrima Jatta, Lamin Barjo, Edrisa Manjang, Mustapha Barrow, Alige Camara, Alkali Barjo, Sanna Manjang, Sheikh Tijane Jatta, Sheriffo Touray, Bunama Touray, Sanna Badjie, Alieu Badjie, Ousman Janneh, Omar Sowe, Mamadou Salu Bah, Tahirou Jatta, Binako Njone, Lamin Jatta, Alieu Jatta, Alige Fofana, Lamin Manjang, Abdou Manjang. “The phenomenon of migration in my country is responsible for too many deaths, too many wives are widowed, too many villages mourn their youth.” The departure of the youth destroys the nation. Nonetheless, it is one of the only means of survival.

It is paramount to understand how Manjang envisions the future of The Gambia. Children are his greatest source of inspiration. The young man is throwing himself into his work, caring for the next generation of Gambians. Most of the time in the river country, kids are easy prey to misfortune. Their juvenile woes increase his determination. He will even push kids in his cart to relieve them of the burden of walking distances he considers inhumane. He often supervises outings to the ocean, the Abuko Nature Reserve, and the Village des Arts. Ultimately, he wants to know more about their existence than the broken line whispered by many of his students: “Mom and Dad don’t have any money.” Still modest, Manjang concludes: “The children in my country are smart. They know how to express themselves and they know how to think critically about the world around them.

Agrandissement : Illustration 18

“When we bring the kids to the beach, they rush out onto the sand at the sight of the magnificent ocean. Some of them even cry.”

Agrandissement : Illustration 19

“Here in the hut, the children study the upper middle class, their careers, their way of life. They already know the cruel difference between the poor and the rich. Misery has followed these kids since their first breaths. What good will their diplomas do them?

On occasion, he sings their favorite song, an ode to equality for all mankind—a song he hopes to soon hear ring true:

Some kids are hazelnut just like bread,

Others are yellow and sometimes red,

Some kids are white and some black,

The color is different,

But the kid is the same.

Manjang punctuates the lyrics with a motto in Mandinka:

“Fansotoo – Karnyang – Baadinya” which means Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.

He offers some last words for us, and for his country: “I aspire to see change. I would like our leaders to realize the magnitude of the problem. For a new, better education. For a new way to perceive the world. In the end, I aspire to eradicate this misery.”

Agrandissement : Illustration 20

Now, patience paces daily life. After walking half an hour, Manjang takes the opportunity to charge his phone’s battery while drinking a cup of tea at Mussa Janneh’s. It's this phone that connects him to the world he aspires to explore. Enjoying life under the shadow of his familial mango tree and next to the cinderblocks that have piled up over the years thanks to the donations and help of friends and family, a solidarity that is now undermined by the pandemic. Patience… and brotherhood.

Clément, Murielle, Cydney, Antoine, and myself are just humble couriers of Manjang’s story; a story that makes us feel irrevocably linked to him and his country. What if we, as a group, could offer him the chance to materialize the dream he has held so dear for so long? Surely, meeting him, even for a short time, in our country that has distinguished itself in the affirmation of great ideals, would make a bit of this world a beautiful village. Don’t shared dreams have a better chance of coming true?