Agrandissement : Illustration 1

Article source: " Polynésie : Éric Clua affirme avoir démontré l’existence de " requins tueurs en série " ", Waldemar de Laage, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 19/11/2024.

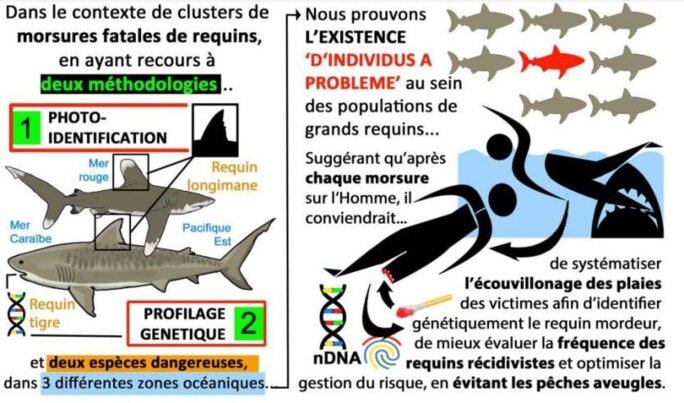

Might the risk of shark attack be isolated to a few problem individuals? Éric Clua has been saying so for years. In an article published in 2018, the researcher specialising in large marine predators hypothesised the existence of “problem sharks”. He described a kind of serial killer shark: “extremely rare individuals who have added human meat to their diet by succeeding, unlike the vast majority of their peers, to feed on humans, which are not their natural prey.” This therefore means that “99.9% of sharks pose no threat”.

Clua claims to have gathered evidence to support this hypothesis, which he has presented in an article published early in November by the scientific journal Conservation Letters, and co-authored by eleven other researchers from French Polynesia, Hawaii, the Caribbean, mainland France, Egypt and Norway. “The 2018 article was based on speculation,” says Clua, “the one step that was missing has just been taken: finding and documenting cases, to show that it is indisputable.”

Three Case Studies

For about ten years, Clua has sailed the seas to find “three case studies”. The first was in the Red Sea, where a female oceanic whitetip shark was shown by “photo-identification” to have carried out several separate attacks. The second was in Costa Rica, where a tiger shark – with a clearly defined modus operandi, involving “attacking divers during decompression stops” – was implicated in several similar attacks around Cocos Island. And the final case was in Saint-Martin, in the Caribbean, “where I was for the first time able to carry out the procedure I’ve been advocating for the past ten years, that is to say swabbing the wounds, which allowed us to demonstrate via genetics that the same tiger shark had bitten someone twice, the two attacks having occurred one month and 80 km apart.”

Proving this hypothesis has almost been a career-defining quest for Clua, who has been “appalled” to see authorities “blindly slaughter” dozens of sharks after each attack, in the hope of “lowering the risk” by reducing the overall population. “This has never worked,” he points out, especially in Réunion and New Caledonia.

Agrandissement : Illustration 2

“Why do we do this to sharks but not tigers, lions, or rhinos?” asks Clua, who is based in French Polynesia, “not to mention human beings. When there’s a killer in Paris, we don’t just cull everyone on the streets hoping that it’s going to solve the issue.” Clua believes that identifying “problem sharks” would make shark control programmes more effective by targeting individuals that pose a genuine threat, “which would not be easy, but it’s certainly not unachievable,” he claims.

DNA Database

The use of DNA profiling, like in Saint-Martin, is a “foolproof method”. Clua would like the process to be introduced as standard all over the world, to compile a database of sharks that have bitten humans. “When a human being kills or rapes someone, forensic scientists and doctors swab to collect the rapist’s DNA,” Clua points out, “but when sharks attack, no one does that.” The idea would be to “do the same thing we do with terrorists: build a database of all the potentially dangerous sharks,” using “individual genetic profiling.”

The man known as the “Shark Profiler” has several other cases in mind, particularly the attacks in Nouméa in 2023, where “I would bet my right arm that it’s the same shark, but I can’t prove it because nobody swabbed for DNA.” If this procedure is applied more widely, it will allow him to gather further evidence.

"Rogue Shark" Controversy

Ever since he first published his hypothesis, it has caused a good deal of controversy among the scientific community. According to Clua, certain specialists have been trying to dismiss his work because they believe it only encourages a false idea popularized by the film Jaws. “These repeat-offender sharks should not be confused with the concept of the ‘rogue shark’ in the film,” he says, “they do repeatedly bite human beings, so that’s something they have in common, but they don’t necessarily enjoy it nor do they prey primarily on humans. Unless proven otherwise, those two ideas can be considered science-fiction.”

“My peers have stuck to the same story for the last forty years. They think that all sharks behave the same way, that they have bad eyesight and sometimes mistake surfers for sea lions,” he says. This is also the position of environmental groups. “But that is a highly dubious argument, it implies that all sharks can make a mistake and therefore that there is a problem with all sharks.”

He does say that “proving that there are problem sharks does not mean that all bites are committed” by problem individuals. “But a significant number of them are […] and that is a new development because up till now, we haven’t had a whole lot to say about sharks, other than they’re a pain in the arse.”

Two Problem Sharks in French Polynesia?

In French Polynesia, Clua recalls the case of an oceanic whitetip shark (known locally as a parata) that bit a swimmer who was taking part in a whale watching trip in Mo’orea. He also cites the case of a tiger shark that tore off the leg of a pearl farmer in Mangareva, two years later. Despite carrying out extensive research, he had never found any previous evidence “of predatory bites in the past 75 years” in French Polynesia. “And now we have had two bites over a period of 5 years that can be classed as predation: one by a parata and the other by a tiger shark. Coincidentally, these are the two species discussed in our article.” He warns that there are potentially two “problem individuals roaming around French Polynesia.”

“We should go to the trouble of monitoring our parata and our tiger sharks,” he suggests, “and we should take the action I recommend, which is to say eliminate the potentially problematic individuals. But for the moment the authorities are not interested.” So, what do we do now? Do we stick our heads in the sand, or do we do what Éric Clua suggests? We should “establish a discriminating and effective system, a kind of database,” he concludes, “I personally think we should handle sharks like we handle terrorists.”

Translated by Jeanne Persem, Maxime Moreau and Leïla Bosseman

Editing by Sam Trainor