ART, POETRY AND GENIUS

CLÉMENT DENIS. UT PICTURA POESIS

This book is a miracle ! my editor at Thames & Hudson told me when after two years of work I handed over at the given date the final manuscript and the 450 illustrations of my book THE ART OF THE CABINET. It is a beautifully produced work of art in itself, I wrote it in English, it was translated in Italian and in French, the latter on Gallica BNF https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb123927189,

My last book CLÉMENT DENIS UT PICTURA POESIS has just been published by the Éditions Lord Byron under the enlightened direction of Laurent de Verneuil, to whom I had proposed the project. It is the first monograph of this young contemporary artist, and it is also a miracle and a work of art for different reasons.

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

It was an unprecedented human adventure which formed part of several years of research in the creative process and the various manifestations of genius in art and poetry, particularly in France. Paradoxically I had initiated it in Rome with my study of the Italian anglophile author, aesthete and collector, Mario Praz (1896-1982). In 1930 he had published a pioneering series of essays on the dark side of Romanticism in a volume La carne, la morte e il diavolo, in reference to Sade and decadent literature which caused scandal. In 1933 it was translated in English and became a best-seller under the title The Romantic Agony. Paradoxically it was only translated in France, which was at the source of its inspiration in 1977, La chair, la mort et le diable dans la littérature du 19ème siècle. Le Romantisme noir. I organised lectures and visits at the Museo Mario Praz in Rome, published several articles in English on Mario Praz, in particular in the British Art Journal http://www.britishartjournal.co.uk en 1999,Vol. 1, N. 1 and wrote a manuscript on commission for an English publisher who failed to publish through lack of finances.

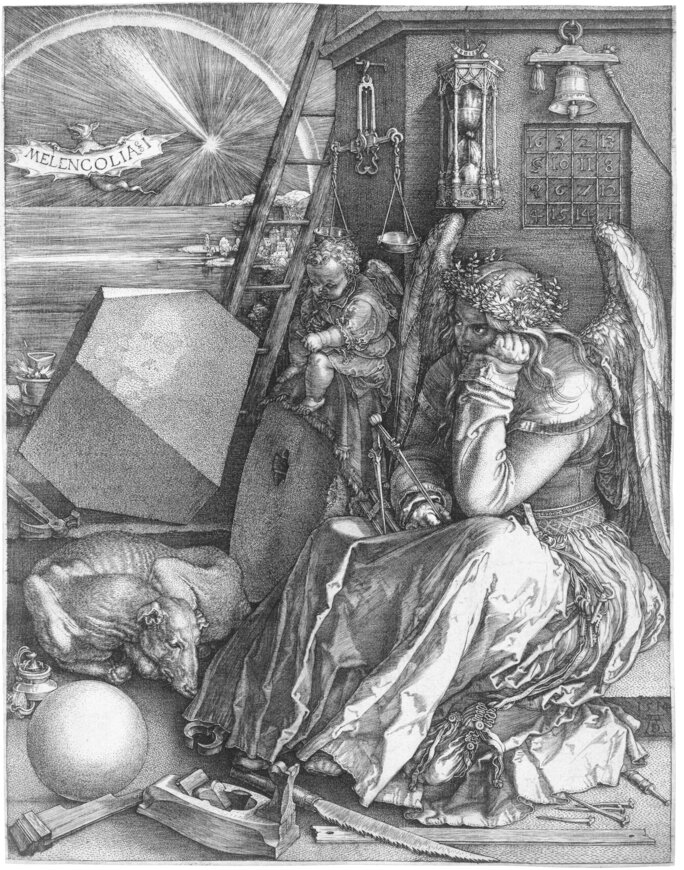

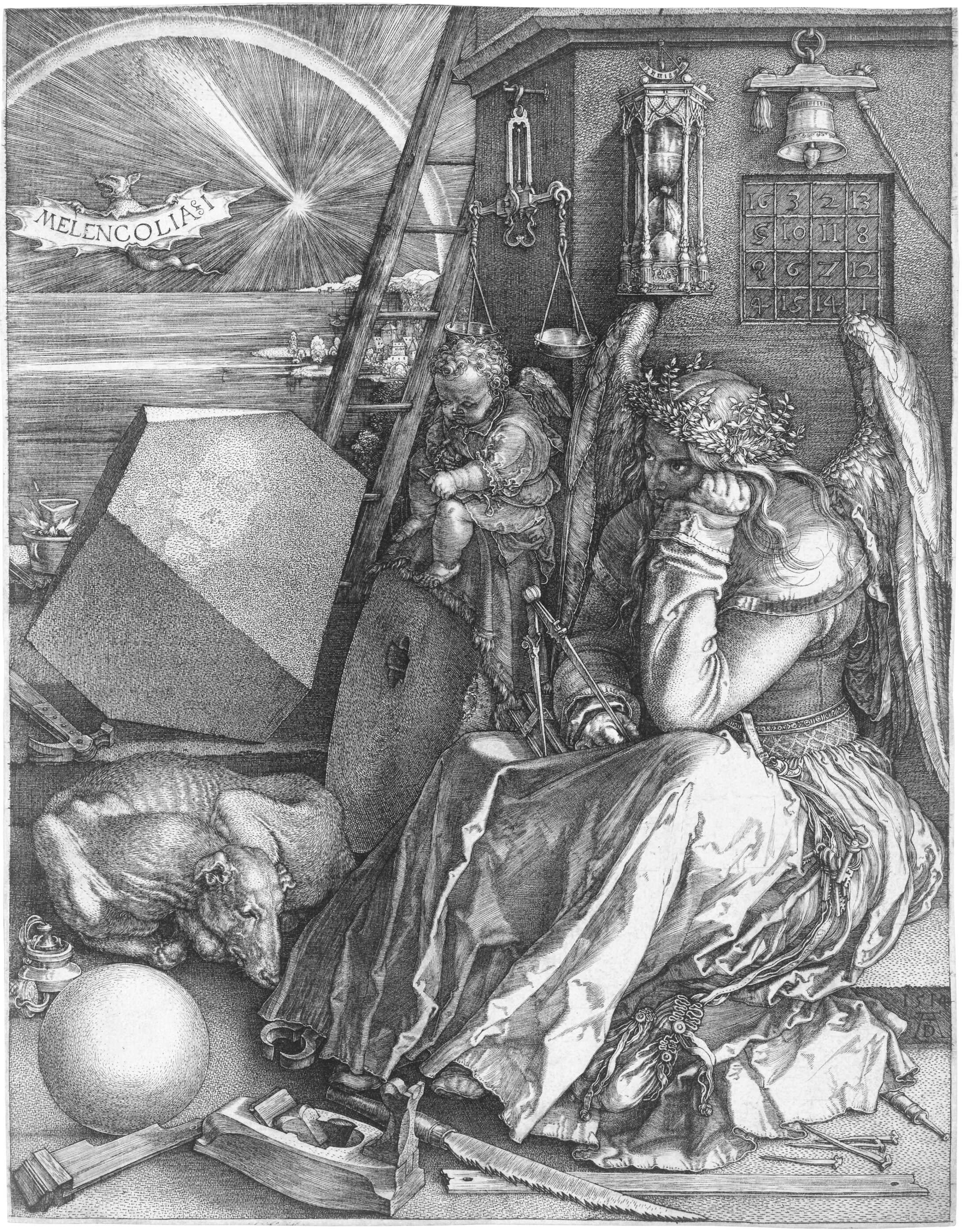

In this study I had analysed in his writings and interviews with his friends and colleagues the nature of Mario Praz’s genius. He was a scholar of encyclopaedic scope on European art and culture in particular of the Directoire, Consulate and Empire periods. In emulation of his friend Paul Marmottan, the French scholar and collector, he had become an expert on the subject. Praz’s temperament presented all aspects of the erudite scholar of the melancholic type described as Saturnian since the research conducted on the subject at the Warburg Institute in London. In 1923 Fritzt Saxl, Aby Warburg’s assistant who had created the Warburg Institute at his death, had published in collaboration with E. Panofsky an essay on Dürer’s engraving Melancolia. In 1964 he wrote together with O. Klibansky Saturn and Mechancholy – Studies in the History of Philosophy, Religion and Art, a subject also explored by two other members of the Warburg, Rudolf et Margot Wittkower in their ground-breaking volume in 1963, Born under Saturn. The Character and Conduct of Artists. And although he never openly acknowledged his debt toward Aby Warburg, Mario Praz was deeply influenced by him and contributed to the first issue of the Journal of the Warburg Studies in 1939 a translation of his 1934 essay on emblems and devices Studi sul Concetttismo, Studies in 17th century Imagery, a study of the allusive, poetical, philosophical and esoteric imagination of the hermetic artistic creation.

Agrandissement : Illustration 2

There has never been an-depth study of the dark side of Romantism in Praz’s work. It reflected France’s dark side, which was an obstacle to the Italian national character. It the same for me, my solar enthusiastic and ecstatic nature does not fit easily with the dark collective shadow of my native land. I had fled from its noxious effects when I was 21 to become British in a less brutal, less violent and less contentious country, in a more open, more tolerant and more respectful society where I could find the opportunities for personal growth, freedom and creativity in my work which France would never have offered me. Yet it seemed that my career as a British art historian was bringing me back to this pitfall. I had to confront it if I wanted to go forward, Mario Praz became my guide and mentor in this challenge I had to face. Back in Paris, where I was connecting again with my own cultural heritage in my mother-tongue, for all human beings uniquely charged with emotion and creativity, I followed Praz’s footsteps. I studied his meetings and exchange with Paul Marmottan, his correspondence among others with Maurice Heine, who was on the same wavelength. After Apollinaire, Heine, had studied Sade’s manuscripts and published them from 1926 onwards. In Paris Dadaism and Surrealism were introducing some reactionary ideas: in 1918 the Dada Manifesto declared : Beauty is dead, and in 1930 Salavador Dali described the Three Cardinal Images of Life: Bood, Excrements and Putrefaction. Praz also corresponded with the Franco-British mystic convert, Charles Du Bos, critic and writer, who declared in 1924 in The Fifth interview with André Gide : To always burn with this fire like a gem, to hold onto this ecstasy, this is the true success of life.

Yet the Roman-born Praz who became Florentine after his mother’s second marriage, did not share this luminous mystical vision, neither did he share Marsilio Ficino’s Neoplatonism. The founder of Cosimo de’ Medici’s Accademia described the Divine Frenzy seizing the soul in its quest for the Higher Realms in its Seventh Letter, De Divino Furore in 1547. Praz had defended a thesis on Gabriele D’Annunzio, subject of the last essay in his volume La carne, la morte e il diavolo, L’Amor sensuale della parola, speaking of it in those terms: carnal aspect of the thought… a sensual instinct purified and exalted at the white fire of my thought … Mystical exhilaration which sometimes brings forth the word from my flesh and from my blood. It echoes Beaudelaire’s praise of this divine frenzy: One must always be drunk…together with the French Symbolist poets, the English and German Romantics Praz translated, and was influenced by their works. His cold and sombre nature made him favour what he described in Montaigne’s art: variety and strangeness, grotesques and monstruous bodies. André Chastel with whom he corresponded saw him clearly as a Surrealist scholar, while Mario Praz described himself as Merlin, son of Satan. Surrealism had an oneiric aspect dwelling in the sombre depths of the subconscious, it is reflected in the magical aspect of Praz’s work, who artfully played on different levels of reality.

The first clinical studies in psychiatry were initiated in Paris under the influence of Jacques Joseph Moreau de Tours (1804-1884). I had discovered his pioneering work through the art of his son Georges Moreau de Tours, a painter. He studied the paranormal and pathological states of the human psyche under the influence of certain substances leading to altered states of consciousness during some gatherings attended by the most influent members of the Romantic and Symbolist movements in art and literature. In 1844 at his return from a journey in the Middle East where he had discovered the use of cannabis, Jacques-Joseph Moreau de Tours had gathered around him artists and writers at the Hôtel Pimodan, now the Hôtel de Lauzun on the île Saint-Louis. There he conducted an exploration of the paradis artificiels described by Théophile Gautier in 1848 in his account Le Club des Haschischins, and by Charles Baudelaire in 1860 in a chapter of the Paradis artificiels. I created an association in order to organize an exhibition on the subject: https://amisdemoreaudetours.com/

Armed with years of research on artistic creation and the nature of genius, I went to Vétheuil in August 2021. A French television documentary producer based in Hong Kong, Richard Heyraud, had contacted me on my website and invited me to visit a young painter of his friends, Clément Denis, for whom he acted as an agent. The young man’s thin and ascetic figure waiting for me on the station platform at Mantes-la-Jolie made a strange impression on me. As I was walking towards him, I sensed in him a previous life as a hermit in the desert in Ancient Egypt. It was not the life of a blessed soul lost in the bliss of divine contemplation, but one of those troubled souls tormented by their inner demons who shunned the world and the commerce of men. I have always been able to read the human soul, and for a long time I thought that everyone could do the same, until I realized that it was not so. This gift also enables me to perceive in some people, for various reasons, some of their previous incarnations. I have used this clairvoyance in my teaching career, in my work and my marriage. It has been reinforced by my experience of the Montessori Method. Its foundress, Dott.ssa Maria Montessori, had studied in Paris with the famous psychiatrist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893). His pioneering work at the Salpêtrière Hospital dealt with hypnosis and hysteria and led to the theory of psychic trauma, in turn influencing Sigmund Freud, one of his students. This teaching method gave me a solid formation based on the respect of the soul’s individuality and integrity. It has been one of the most important aspect of my relationship with others, it allowed me to adapt to various cultures and happily be integrated in the ways of different countries.

I put it all to good use in my relationship with Clément Denis. I had no other information about him other than some links to his website and visual documentation on his work, which I saw of high quality. I then accepted the invitation although I did not know who I was dealing with besides the fact that we both came from the Loire Valley, his agent had told me. He also added that Clément had recently settled in Vétheuil in Claude Monet’s former home. He lived there from 1878 to 1881 and painted 150 canvases before moving to Giverny. His first wife died there and is buried in the village churchyard. The small craftsman’s house stands on the side of the road overlooking the sloppy meadow at the bottom of which Monet had his studio on a boat on the river Seine. The house is sadly deprived nowadays of its former rustic character. The owner had it renovated in a petit-bourgeois taste without imagination and used it as a bed and breakfast until the Covid epidemic, when she let it in July 2021 to Clément Denis and his companion. As I came in the tiny entrance I noticed the old wooden staircase covered with carpet and a sign on the doormat saying: Please wipe your feet! I thought amused that Monet would be turning in his grave…

Agrandissement : Illustration 3

Lunch was a long monologue from Fouzy Mathey, Clément’s companion. She recounted for me in detail her life and numerous misfortunes, leaving Clément silent on my right side, although I was trying to find some common subjects of conversation not knowing what to make of it all. As time was moving on and I had to catch a shuttle to return to the station at Mantes-la-Jolie, I finally asked if I could after all see Clément’s work? I was led in the courtyard where under an awning I was struck by a large painting named Purgatoire, I was told, showing some figures in an icy enclosed space. Clément told me that they were wandering souls, and I was enthralled by the powerful force created by the forms depicted in sombre colours moving into the light. I only had a small half hour to assess his work in situ, while he was spreading on the gravel the large sheets of Arches paper on which he paints in acrylic. I saw some majestic and tormented landscapes in an Expressionist style and violent colours, and some Surrealist and allegorical scenes in the same style. I was commenting as we were moving along, prompting him to describe them. Fouzy who was following us remarked amazed: No one has ever said that about Clément’s work! I took in without comment the admission of her lack of understanding and send an email to Hong Kong asking for a clarification of the reasons of my visit considering the situation. I received an immediate answer: if we could come to an agreement on terms and conditions, the agent would finance a book on Clément in French and in English, and no he was not interested in Fouzy’s projects.

Agrandissement : Illustration 4

Like Mario Praz, Clément Denis belongs to the Melancolic type according to the Humoral theory as defined by Aristotle and Hippocrates: dry and cold, ruled by black bile, under the influence of Saturn, it is an earth sign, symbol of winter and old age. They are both cerebral without empathy for others and can sometimes display pettiness and a manipulative petit-bourgeois behaviour, as I have observed. They lack generosity of heart and mind, they are loners who live in their own world, although Praz was an excellent and generous teacher and loved women, and Clément Denis communicates with the world round through his art. But it is in the world of Ideas, not the world of the living, which are never represented. Besides he has a difficult and contentious relationship with women as he suffered psychic traumas at their hands as a child. Death is omnipresent in this sombre temperament. Praz cultivated its evocation in representation with art and erudition in his writings and his art collection. Clément flirted with it several times in repeated suicide attempts.

Our second meeting took place in Paris and on his agent’s advice, who had suggested that I should take him out of doors to make him talk, I invited Clément to a picnic at the Medici Fountain in the Luxembourg Garden, it is one of my favourite places in Paris, full of grace and beauty, reminding me of Italy and Florence. There sitting in the sunshine and away from the constraining presence of his companion, he relaxed and talked. To put him at ease I talked about my own international path of life, assuring him that I could understand everything, and that nothing would be published without his agreement. We chatted about the subjects of interest to him at that stage, as far as I remember esoterism, spiritism, his family and childhood in the Loire Valley. I had already prepared a preliminary synopsis of the book and we agreed that I would send him a list of questions for him to answer. I had to chase him up for an answer, eventually it was done in a telephone interview which enabled me to write the first chapter. Weeks passed by, eventually he gave me a date for a second visit and the opportunity of spending a night on the spot, allowing me two days of work. I presented him with the text which we reviewed together. But when he wanted to show it immediately to his companion for her approval, I firmly refused as I did not want him to be influenced by her before the final draft. I had quickly realized that she blew hot air, acting as a victim and wanting to attract to herself the attention I gave to Clément and his art, which she did not understand. When before leaving I gave her the text to read, I heard him murmur She is perfect! And I knew that I had won his trust.

Before starting any writing, whether for a book, a poem, or an article, I need to find the right note just as in music or singing. Once this note is set I steadily keep it until the completion of the work. Clément had recalled for me the story of a very painful and poignant childhood. I then knew that I could only handle all its sordid aspects and suffering if I sublimated it in spirit to the level of art and poetry. I then turned to the metaphysical poetry of the Persian 13thcentury Sufi mystic, Djalâl ad-Dîn Rûmî, his luminous spirit imbued with love would guide my inspiration in the writing of the book. This time I could study Clément’s work in situ, and it dazzled me. Of course, I needed more time to study it at leisure, but this was not offered and in the circumstances I did not want to impose myself. My experience, my visual memory, and the intuitive relationship which grew instinctively between us allowed me to compensate for the lack of time. I scribbled hasty notes as I listened to his commentary while he was spreading his works on the courtyard gravel. We had found in this study a perfect harmony of mind expressed in few words, we started and finished each other’s sentences, effortlessly slipping from on subject of another, the one enlightening the other and vice versa. This intellectual and spiritual understanding allowed me to progress very fast in my work.

The moment came when I wanted to understand the relationship between he and his companion, it was the only interview I conducted with both of them. Clément’s agent had qualified it as muse. At once they both refuted it, she presented herself as a a collaborator like Christo’s wife, which was clearly wishful thinking since she obviously did not understand his work and was not equal to the task. When I pressed them to explain, they both fell silent and I understood that their relationship was on another level of psychic dependency which I sensed as toxic, they had met through an exhibition on Death. And in my experience, and in his agent’s own words, she used to push herself forward to the detriment of Clément, even if he remained ignorant of her manipulations or denied them for his own reasons.

A second visit to Vétheuil became necessary to edit the final text together after weeks spent in cancelled appointments, lists of questions left unanswered, telephone conferences postponed, delays piling up and making my life very difficult. I was going forward in the fog, gathering snippets of information to slowly build up a clear vision of this artist’s work. He was avoiding the issue with fuzzy pretexts, playing the diva, and flew in a fit of hysterics when I firmly refused his companion’s intrusion in the project.

She wanted to dictate my work, and he wanted to use her as a screen, the Hong Kong agent had to intervene, Clément apologized, and we renewed the dialogue. But it had become clear that I had been commissioned this work in the naïve assumption of purchasing the services of a ghost-writer, to use my name and personal reputation to give this monograph prestige and credibility. Yet all involved were trying to influence it and turn it to their own interests and advantage, including the agent who openly stated noy knowing anything about art history, nor what humanism means, but kept insisting that the book according to him was collegial.

I needed all my experience of people management and use of diplomacy for the manuscript to be completed and delivered on December 1st 2021 as per contract. I knew that I absolutely needed to surf on the crest of the energy which had been generated or the book would never see the light of day. To do so I needed to keep a fragile equilibrium with the very persons who wanted to undermine my work instead of supporting it, and to stay the course in my scientific analysis of Clément’s art without entering in an over-indulgent and reductive psychoanalysis. I wanted to to keep the poetical and metaphysical note which would endow the volume with a humanist dimension beyond a simple art history monograph. It appeared essential to me given the nature of the artist and of his art. From the beginning I had senses the influence of Germany on his work not only from the Expressionist artists of the early 20th century but also from literature when we spoke about his readings. Yet it was only after several weeks when he was putting forward some of the contemporary French artists who had influenced him that he casually mentioned the name of the giant I was waiting for, Georg Baselitz. It had been obvious to me from the very beginning, I knew the artist’s work and his son Daniel had been one of my students at Sotheby’s in London. I then perceived in Clément the same reticence I had met with Mario Praz in not acknowledging the debt they owed to former masters who have preceded and influenced them. It took nothing away from the value of their own work, but showed in them both a lack of gratitude and humility

Beyond these human foibles, the work of ten years of this young man’s life seemed to me astonishing. He feels himself following the path of suffering, he had sublimated it in his first years as an artist in exorcizing his inner demons by absorbing and making his own all the avant-garde art movements of the 20th century, as recognized by one of his teachers. Having done so he had developed his own very original style of painting in acrylic on paper. Working in a creative frenzy, applying the colour with his hands, he had touched upon all the great crisis causing havoc and destruction in Europe and the world in the 20th century. Like Baselitz he worked in series, depicted the Two World Wars, then the great causes of the first two decades of the 21st century, the alienation of man in a world made inhuman by the destructive effect of the law of the market due to globalisation, immigration, and climatic change.

For me who share in the mystical experience of Charles Du Bos: To always burn with this fire like a gem, to hold onto this ecstasy, this is the true success of life. I saw in this young man’s the same creative force at work in him as in me. Ii is the force of the Robbers of the Divine Fire, as defined in 2003 by Dominique de Villepin in his Éloge des Voleurs de Feu, an exegesis of French poetry: In the poetry of the ‘Voleurs de feu’ can be found the awareness of a lost unity to be built anew. I wanted through the art of my writing, as I recounted and put forward his own testimony, to reveal him in an initiatory maieutic, to hold out a mirror to him, to make him aware of the soul-group he belonged to, and of his own achievement. I was struck by the outstanding visionary aspect of some series: No man’s land, Winter is coming, Les nomades immobiles.

Agrandissement : Illustration 5

The last one Le chant du fleuve speaks of the climatic change, the rising of water, it is a synthesis of all his previous work and will remain I think, his most important work to date. In considering those vast panels the sense that they were maybe his testamentary work came over me. I felt in them a finality, that it would be very difficult for him in the future to rise again to such a level of fusion of concept, content and execution. He was then going back to his sources at Vétheuil with the landscape and he told me : I always paint the same landscape…He has reached the summit of artistic creation on the strength of this inner fire that nourishes and consumes him. But I know by experience that on the journey of the human soul on earth, for the Voleurs de Feu ‘s maturity to last in time, an awareness of this creative force and its control are required. Those who are touched by the wing of genius pay a heavy tribute for their creative talent, and they must have a strong and clear mind to resist to the illusions encountered in the realm of Ideas which forbid access to the souls not yet well forged at their fire. The psychic fragility of this artist who so longed for death, but who has created a remarkable opus of work in choosing life despite his sufferings, is a weakness he will have to overcome. At each stage of life the evolved man must renew his choices in sublimating them consciously to a higher level. Clément Denis predicts himself a short life and an early death, he does not care about posterity, he knows instinctively that his days are numbered. There is a poignant greatness of soul in his own personal and artistic pursuit which puts him to the level of these visionary Phares, Beacons, whose destiny is to enlighten others as mentioned by Baudelaire in his eponymous poem, with which I close this book in homage to the art of a tormented soul, with a very particular destiny.

Agrandissement : Illustration 6

Monique Riccardi-Cubitt

Paris, 9th April 2022

Monique Riccardi-Cubitt

Clément Denis. Ut pictura poesis,

Paris, Éditions Lord Byron, 2022

Edition of 220 copies numbered from 1 to 220.

Hardcover, 24 x 30 cm, 196 pages

French English edition

ISBN 978-2-491901-23-3

35 €

Éditions Lord Byron

10, rue Lord Byron, Paris 8e