It was a Friday evening, and storms raged over Paris. Working in his office in the Paris headquarters of Amnesty International, Gaëtan Mootoo told his wife Martyne Perrot, and also his son Robin Mootoo, not to wait up for him because he was working on preparations for his next mission, which was a visit to the town of Gao in Mali, West Africa. He was doing so with all the conscientious detail that always characterised his work.

He was due to leave on Tuesday May 29th, after the marriage of a goddaughter that was to be celebrated on the Saturday, but also after the funeral of the son of friends of his, to be held on the Monday.

The night before, he had dined with one of his colleagues from Amnesty International’s Africa bureau, based in the Senegal capital Dakar, which was a warm and friendly event. During that day of Friday, he busied himself with preparing his family’s summer holidays, and had taken care to prepare a gift of tasty dates which he intended to offer to his Malian friends during the Ramadan.

But he would not return home that night of Friday May 25th 2018. That was when he put an end to his life, there in his office in the Paris headquarters of Amnesty International, where he had served as the NGO’s researcher for West African affairs since 1986 – a period of 32 years. For his family, his close friends and associates, and his colleagues, the news came as an enormous, thunderous shock, all the more so because nothing had indicated to them that such an irremediable event was about to happen.

At most, Gaëtan sometimes spoke of his fatigue, but did nothing to take up rest; he was involved in one mission after another, constantly heading off into the field. While every suicide is accompanied by an irreducible element of mystery, it is certainly within his work that lies the key to Gaëtan’s decision; the workload, working conditions, and the suffering caused by his work.

In a text which he took care to print out, before adding a few handwritten notes, Gaëtan Mootoo explained this. Having found himself alone following an internal re-organisation in 2014, he explained how he had asked for help which had not been followed up. Declaring that he enjoyed what he was doing, and that he wanted to do it properly but could not see himself able to continue in this manner, he wrote: “Which is why I have made this decision”.

Within Amnesty International, whether in London, where the general secretariat he served was based, or in Paris, where he had his office at the French branch of the NGO, the shock what happened is immense, as expressed in this statement (in French) from Philippe Hensmans, director of Amnesty International Belgium, and also here by Salil Shetty, secretary general of Amnesty International.

Two internal investigations have been announced by Amnesty International, one by the French administration, the other by the international administration, with the aim of explaining what led to the suicide of Gaëtan Mootoo and also to establish what lessons might be learnt. In a letter addressed to Gaëtan’s widow Martyne, Amnesty International’s secretary general Salil Shetty insisted upon his “personal determination that our organisation as well as the whole of the Amnesty movement understand all the lessons of this tragedy”.

In face of such an unprecedented event in the history of the pioneering NGO for the defence of human rights, past and present staff of the organisation have demanded its international bureau conduct an inquiry that “must be carried out by a transparent, fully independent and impartial external body”, and that Amnesty International should oversee such an investigation with “the same honesty and integrity it demands from governments all over the world”.

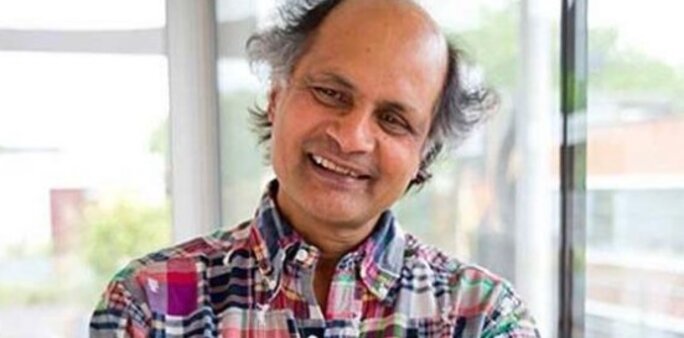

Gaëtan Mootoo died at the age of 65, and had spent half of his life totally devoted to his work with Amnesty International. Not for him the benefits of ‘air miles’ rung up on his travel cards – he believed that belonged to the NGO and not to him. In the same manner, he questioned the fees he was offered for giving lectures (in English) on human rights and humanitarian missions to Master degree classes at the Paris political sciences school Sciences Po, arguing that this was about his experiences which belonged, as it were, to Amnesty International. But beyond his scrupulously ethical behaviour, the essence of his work is to be found in his concrete actions in the field which, following his brutal disappearance, have been unanimously praised in Africa.

Later, when history books will tell the stories of the democratic transitions in West Africa since the 1980s (and their vagaries), the name of Gaëtan Mootoo will count for more than the names of the numerous politicians who were the actors or beneficiaries. “Gaëtan Mootoo was the African of Amnesty International,” wrote, in the best-informed homage that has been published, Alioune Tine, who was Amnesty International’s West Africa director based in Dakar until becoming, at the end of 2017, an independent expert for the UN on human rights in Mali. “Because, during almost 40 years, he lived through all the political crises, armed conflicts, the tensions followed by serious human rights violations, whether in Guinea-Conakry under the regimes of Lansana Conté and Captain Dadis Camara, notably during the events of September 28th 2009, whether in Togo under the authoritarian Eyadema regime, or whether also during the post-Houphouët crises and conflicts in Ivory Coast, or, finally, in Burkina Faso with the Norbert Zongo case and the popular insurrection of 2014.”

But also in Senegal, where, wrote Alioune Tine, “Gaëtan worked from very early on and acquired a proper experience of the Casamance conflict and the political crises that preceded political alternance in 2000”, and above all in Chad when, under the reign of Hissène Habré, Gaëtan Mootoo accomplished “a titanic task”, revealing, even while the regime was still in place, the existence of “torture, arbitrary arrests, extra-judicial executions and forced disappearances”. To this necessarily incomplete list should be added his two last reports, about the zone of the Sahel region where the French army is engaged in military action through its mission Operation Barkane. One of these reports, dated April 2018, concerned Mali, with the worsening of the security crisis and the discovery in the centre of the country of a mass grave. The other, published in May, concerned Niger and the deportation of more than 100 Sudanese to Libya where they were placed at risk of serious human rights abuses, including torture.

“Gaëtan,” wrote Alioune Tine, “had knotted contacts with all sections of society: the dissidents of all kinds – politicians, union officials, activists, journalists, women’s rights activists and African citizens – are all orphans. We all owe a debt to Gaëtan Mootoo who was a shield against the arbitrary. He also contributed greatly to creating the conditions for political alternance in Africa, allowing the dissidents of yesterday to reach power; presidents Wade, Alpha Condé, Gbagbo, and Ouattara would not disagree.”

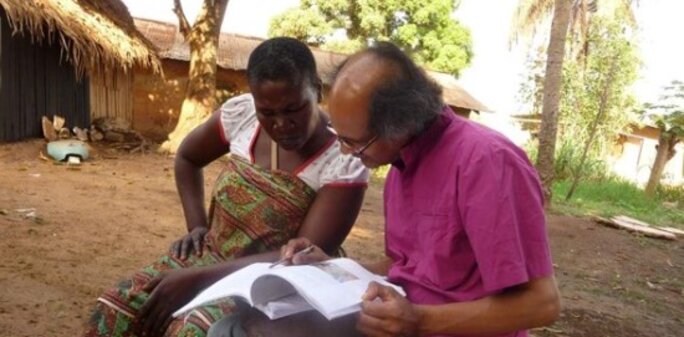

This February, I saw Gaëtan at work in the Malian capital Bamako. A man who spoke with few words, even often quiet, he had that special talent of knowing how to listen in silence, of how to put someone at ease and in trust simply through his presence, which exuded empathy. The word which comes to me while thinking of him is “halo”; he released a sort of calming light around his person, like a ring of confidence that was inspired by his gentleness. It is an image that goes well with the idea I have of what was, ultimately, his life – a mission, a total dedication, an infinite selflessness. The last time that we met, a short time before his death, we agreed to meet up at the end of June in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, on the occasion of the second Sommet des africtivistes (“Africtivists Summit”) where I hope he will be paid homage.

But the portrait is still incomplete. What should be added to it is the dandy-like elegance that was his trademark. One of his mottos could have been along the lines of ‘knowing how to keep one’s dignity in all circumstances’, to ‘never let oneself go’, a principle he stayed true to right up to the manner in which he chose to end his life. Gaëtan Mootoo never left on a mission without the writings of Shakespeare, a teapot and some shoe polish. The Sonnets or The Tragedy of Julius Caesar were his favourite works by Shakespeare, which he read in the original English, the language which was his true tongue of the heart and which co-habited with the Mauritian Creole of his childhood, and French from his bilingual education. His shoes were always impeccably polished, and in the field he exhausted his colleagues by contenting himself with drinking tea all day long, in the manner of a desert nomad.

Always dressed in spotless, often patterned shirts, he detested the baggy jackets made up of multiple pockets that humanitarian workers and reporters so often favour. In sum, upright, and no slacking! In short, self-demanding. But these words that I write remain incomplete and imperfect because they may wrongly give an impression of a stiff and austere nature. Gaëtan enjoyed laughing and telling jokes, walking and discussing, discovering and enjoying. He was also an outstanding cook, marrying flavours with skill.

Respecting his naturally reserved manner, I didn’t know how to pierce the shell he had built, and for which his elegance no doubt acted as the cement. But for the survivors that we are, I would like to suggest, with the help of his wife and son, Martyne and Robin, that one cannot understand Gaëtan Mootoo without bringing into the picture his native country, Mauritius.

This distinction in the form of distance, this difference that was his exception, seem to me to be anchored in his childhood and youth in one the lands of creolisation. Born on September 29th 1952 at Eau Coulée, a neighbourhood in Curepipe, the second largest town on Mauritius located at the centre of the island, Gaëtan grew up in a poor family. He was raised by his grandmother after his mother died while giving birth before he reached the age of two. His grandmother, a school teacher, raised together 13 children, as poor communities that live in solidarity know how to. One day Gaëtan asked his grandmother why they were poor, and she replied that if he looked around himself he would see that that was not the case, but that, quite the opposite, they had incalculable riches. But as he looked around, he could see only the items of a house where there was no wealth. His grandmother then showed him what he hadn’t picked out because it was part of his daily surroundings: a rough bookcase with a few works on the shelves.

Gaëtan Mootoo was part of a long history in which culture and knowledge are the arms of the underdog, the oppressed and the dominated. After his secondary school studies he chose to go to an École normale teacher training institution, before taking up a post as a primary school teacher for five years in Mauritius. His hierarchy considered he was too lenient with his pupils, preferring to educate them with kindness rather than under duress. One day the headmaster entered one of his classes unannounced and expressed his surprise that the pupils did not spontaneously stand up when he did so. Gaëtan’s pupils, schooled in his free-thinking manner, replied that they hadn’t got up because he hadn’t said ‘Good day’ when entering the class. Such was the context of the time, the 1970s, the environment in which he progressed while Mauritius, a former British colony, invented its independence which had been proclaimed in 1968.

Following Gaëtan’s death, one of his close friends, Jean-Clément Cangy, wrote an article published in the mostly French-language daily newspaper published in Mauritius, Le Mauricien, in which he recounted their early years. “It was on leaving college and as young adults that we got to know each other, poking our noses into social organisations here and there,” he recalled. “That was how we became engaged within the Institute for Development and Progress (IDP) with Jean-Noël Adolphe, a formidable unifier of energies. The training in social leadership and in community development always drew packed classes of young people eager for social work, as much in urban environments as in rural ones. We were also present when the Fiat movement was given its baptism. And when priest Reynolds Michel, after twice expelled from Europe, found himself in Mauritius, we joined with him to found the Christian Movement for Socialism (MCPS) and, along with others including Percy Lafrance, Rowin Narraidoo, Jean-Baptiste Cotega, Louis Boullé, Sybille Masson and Désiré Mallet, we broke down the barrier between Christian faith and Marxism, and did so to demonstrate that one could be both Christian and socialist.”

We owe Gaëtan Mootoo’s choice of anchorage in France to the upheavals in the country between May and June 1968. He was primarily of anglophone culture, and if he left Mauritius he might normally have headed for Britain. But he had heard of the Université expérimentale de Vincennes, close to Paris, which was created as a result of the student protests in 1968 (and which today has become the University Paris-VIII Saint Denis). Inspired by the innovation of the project, Gaëtan enrolled in 1978 as a student in its Education Sciences department where he worked on a master’s thesis about the history of education in Mauritius, under the guidance of French historian Georges Vigarello. A penniless student, he lived from doing small cleaning jobs with companies and private individuals, teaching literacy classes, and also grape-picking – he would recount his experiences in the Languedoc region in the same way others would talk of the exoticism of far-off lands. After subsequently enrolling in a seminar course on African anthropology, he tried to find fulltime work – but in vain, such as it was that he came up against that invisible wall which in France blocks the paths of non-whites, Africans and those from the French West Indies.

It was no doubt the hurt of that which explains why he never took up French nationality despite marrying, in 1985, a French national, Martyne Perrot, an anthropologist with France’s national scientific research centre, the CNRS. Gaëtan’s son Robin resumes the situation thus: “Dad adored French culture, but never recognised himself within the nation.” When Martyne and Gaëtan first met, she was carrying out research into the phenomenon of Mauritian women who married French farmers with whom they had come into contact via postal correspondence. Many settled around the country in rural départements (counties) like the Lozère and Aveyron in south and central France, or Finistère in the north-west Brittany region. Her research produced a book, published in 1983, called Les mariées de l’Ile Maurice (The wives of Mauritius Island). It was another type of journey, in one sense chosen and in another sense imposed, the symbol of an inter-dependent world in which an opening is found through relationship.

Rather than obtaining French nationality, Gaëtan Mootoo dreamt of being granted a Person of Indian Origin (PIO) card, a document issued by the Indian government which recognises a person’s Indian origins, which in his case was his Tamil family whose members left India for Mauritius at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.

To journey, to risk, to live and to die… One of Gaëtan Mootoo’s most striking investigation reports, carried out in collaboration with his colleague Salvatore Sagues – who was his close partner up until the reorganisation at Amnesty International in 2014, when Gaëtan found himself on his own – was entitled Giving Life, Risking Death. It was about the maternal mortality rate in Burkina Faso, and bears witness to the essential humanism of his approach. Gaëtan was not solely interested in great political dramas, but was concerned about daily matters like health, schooling and equality. What was to be his latest mission, to Gao in Mali, one which he will now never complete, concerned the obstacles for girls in being able to access education, obstacles imposed by sectarian religious ideologies that come from Islam.

It was in 1986, replying to a job advert published in French daily Le Monde, when Gaëtan Mootoo at last found his home port: Amnesty International, the pioneering NGO founded in 1960 for the defence of human rights by civil society. From that point he felt definitively in debt to the organisation which recognised and accepted him, with no prejudice or reticence. Ever since, he has travelled extensively across West Africa, listening to its societies, giving as much credit to those living in obscurity as to those in prominence, never seeking to make a career out of the misery of the world, but rather acting as a sort of lay missionary for solidarity beyond national borders and for the common causes for equality. Tragedy was often present during his travels, both in the literal and figurative sense. In the field, he was continually confronted by the very worst of things, discovering mass graves, listening to the accounts of those who had been tortured, and once narrowly escaping death by a stray bullet while in Abidjan, in Ivory Coast.

When he was back in France, he added to all this, with a bulimic appetite that astonished us all – and which also intrigued us – a keen interest in the stage and dramas, reserving seats in advance in the most diverse types of theatres, including for the most improbable plays and at sometimes far-flung locations. One month before his death, he had invited a dozen young people to a presentation, in the Paris suburbs, of a Palestinian play, Roses and Jasmine, performed in Arabic with subtitles. He also enrolled several colleagues from Amnesty International to see the performance of a play by Ivan Turgenev, A Month in the Country, in which Anouk Grinberg played the lead role. But his favourite plays were the works of William Shakespeare, and he travelled to London to see a recent new production of Julius Caesar.

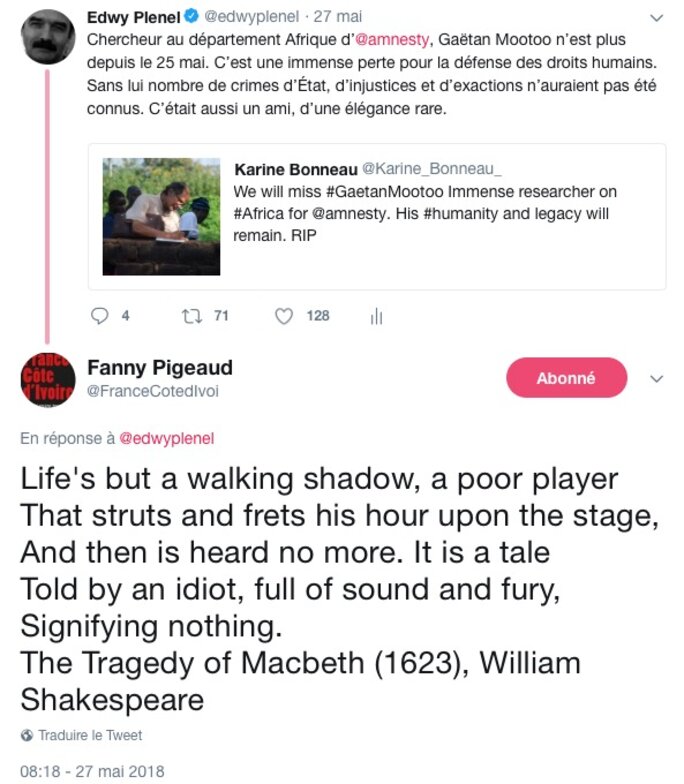

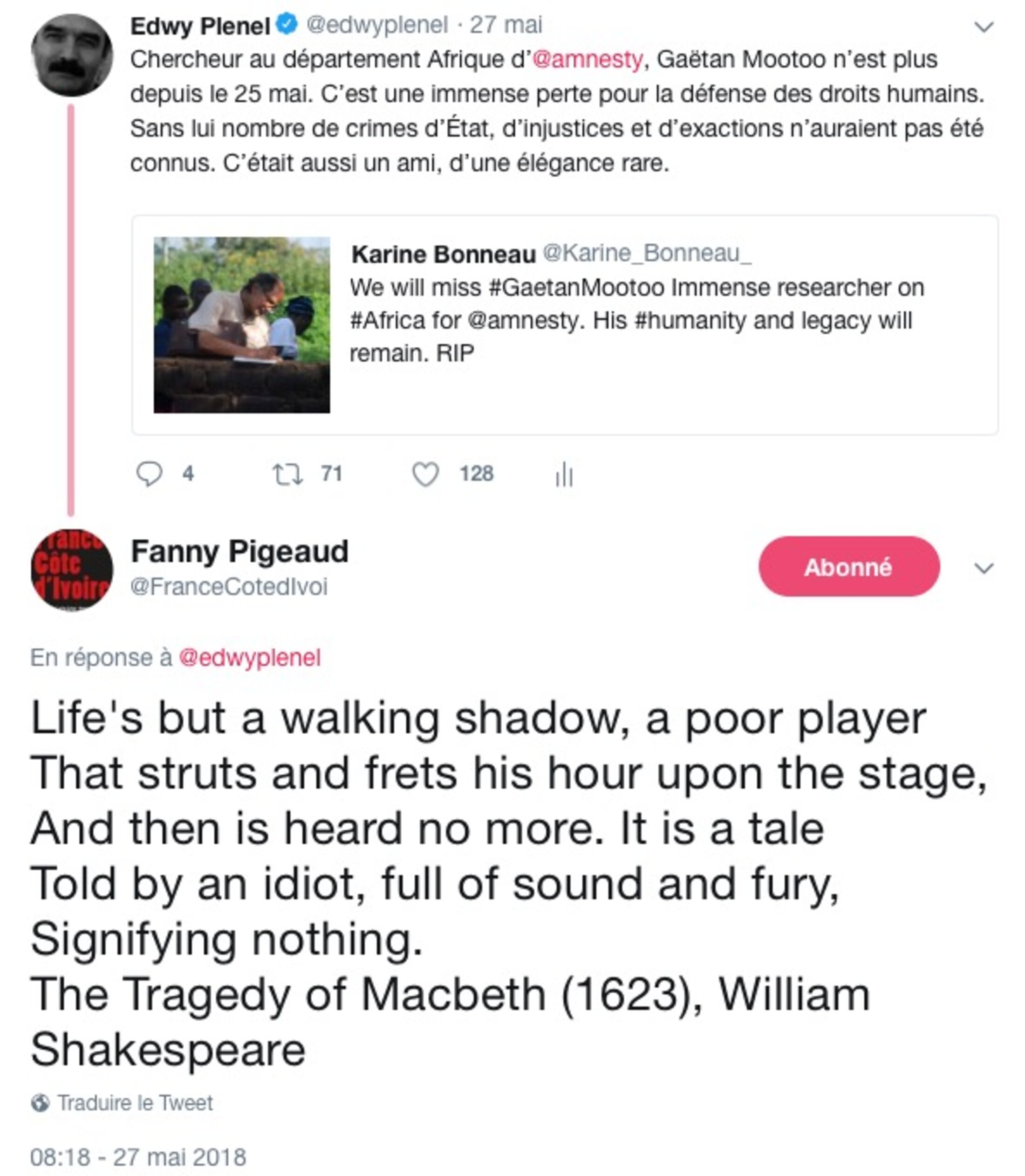

Following the announcement of his death, Fanny Pigeaud, who reports for Mediapart on parts of West Africa and who knew Gaëtan Mootoo well, paid tribute to him in a message on Twitter in which she cited lines from the final act of Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, when Macbeth reacts to the suicide of his wife (see below).

Agrandissement : Illustration 8

In the formal announcement of his funeral, which will take place at 1.30pm on June11th at the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, Gaëtan’s family, his wife Martyne, his son Robin and his brother Christian, chose other quotes from Shakespeare’s works and which resonate so very well with the elegance of this just man, Gaëtan Mootoo.

The first is from Hamlet:

“He was a man, take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again.”

and the second is from Julius Caesar:

“Men at some times are masters of their fates”.

Farewell, Gaëtan, noble heart.

English version by Graham Tearse

The original French version here.