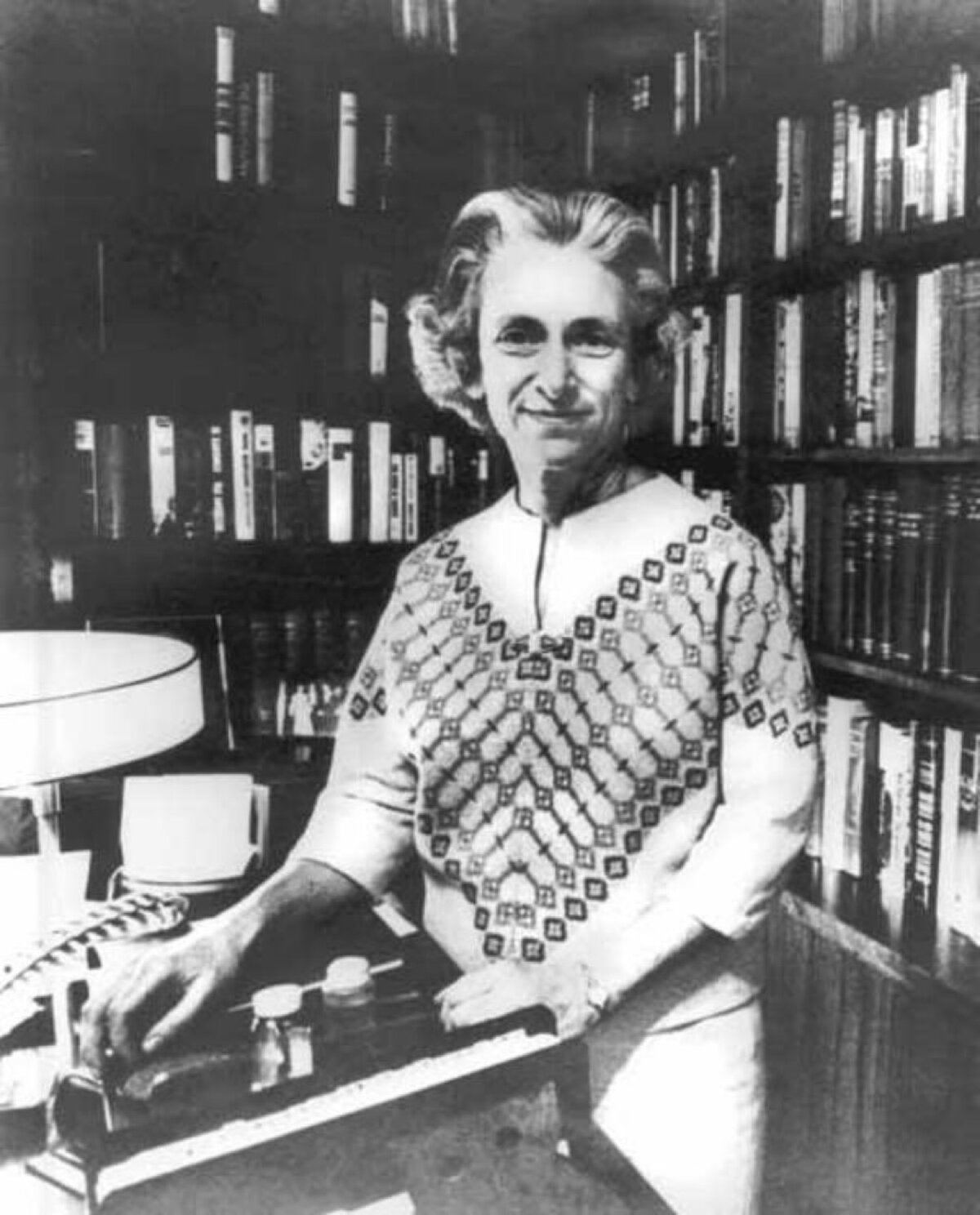

Agrandissement : Illustration 1

Quite remarkably, I kept my New Years’ resolution this year: “Make 2020 a Visionary Year!” It sounds cheesy, yes, but I mean it sincerely.

Even more remarkably, I am leaving this year with even more optimism than I had when it began. Because I see things even better now. And no matter who is in the White House come January 20th, 2021, my vision will be more encompassing than it had been my whole life to date.

You see (pun intended), the trick is not to forget that there’s a full story, and instead to look at some parts of the story too closely. But most importantly, when you consider the full story to seek knowledge and understanding of it through compassion —humanity.

This quote comes to mind from Barbara W. Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century: “Disaster is rarely as pervasive as it seems from recorded accounts. The fact of being on the record makes it appear continuous and ubiquitous whereas it is more likely to have been sporadic both in time and place. Besides, persistence of the normal is usually greater than the effect of the disturbance, as we know from our own times. After absorbing the news of today, one expects to face a world consisting entirely of strikes, crimes, power failures, broken water mains, stalled trains, school shutdowns, muggers, drug addicts, neo-Nazis, and rapists. The fact is that one can come home in the evening—on a lucky day—without having encountered more than one or two of these phenomena. This has led me to formulate Tuchman's Law, as follows: ‘The fact of being reported multiplies the apparent extent of any deplorable development by five- to tenfold’ (or any figure the reader would care to supply).”

Tuchman has written that it has been the method of dealing with the working class since the 14th century. The church and aristocracy worked to keep the masses illiterate and working in the fields to support them.

Read those two sentences again.

But the truth is, we all possess the 20/20 vision, we just have to find the courage to sit and be patient with the unknown and unfamiliar circumstances until the full story reveals itself. This requires faith and trust to navigate the course, especially when the waves are rough. Because the media is owned by today’s “aristocracy.”

Barbara Tuchman is very important and matters a great deal to me. You see, despite being part of the world’s top elite and the crème de la crème of Manhattan, she was able on her own accord to write about history in literary terms, dismissing political influence.

Barbara Wertheim Tuchman was an American historian and author who won the Pulitzer Prize twice, for The Guns of August (1962), a best-selling history of the prelude to and the first month of World War I, and Stilwell and the American Experience in China (1971), a biography of General Joseph Stilwell.

Barbara Wertheim was born in 1912, the daughter of the banker Maurice Wertheim, an individual of wealth and prestige, the owner of The Nation magazine, president of the American Jewish Congress, prominent art collector, and a founder of the Theatre Guild. Her mother was the daughter of Henry Morgenthau, Woodrow Wilson's ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Despite her social status she was herself committed to intellectual honesty.

From an early age, Tuchman, who grew up on the Upper East Side and Park Avenue, rubbed shoulders with the nation’s cultural and political elite. Her mother was part of the Morgenthau clan, making Tuchman the granddaughter of Henry Sr., ambassador to the Ottoman Empire during World War I, and niece to Henry Jr., secretary of the treasury under Franklin Roosevelt. Robert Morgenthau, Manhattan’s legendary district attorney, was her cousin.

Though she wrote about historical events, Tuchman’s relations with professional academic historians were uneasy. According to her, her lack of academic title and graduate degree was a benefit: “It’s what saved me. If I had taken a doctoral degree, it would have stifled any writing capacity.”

She accused historians of producing over-detailed studies that were unreadable. Instead, she preferred the literary approach. She was not a historian’s historian; she was a layperson’s historian who made the past interesting to millions of everyday readers.

Tuchman rejected the academic practice of prefabricating historical systems: "The historian who puts his system first can hardly escape the heresy of preferring the facts which suit his system best.” I agree with her. An association with heretics is impossible.

Barbara Tuchman was born to a patrician family, but her quest for knowledge became her quest for truth. I adore her.

My writing on this site about the War Lobby is a tribute to Barbara Tuchman’s powerful history of the 14th century, in A Distant Mirror —a story of plague, war, brigandage, bad government, insurrection, and schism.

Tuchman showed how these realities resulted in unrest among the lower classes, a failure of will at the top, and a pervasive sense of disintegration, an atmosphere in which a “cult of death” flourished. I have used no less than those same words.

The War Lobby can be expressed more simply as the cult of death. This is why the conspiracy theory about satanists running things behind the scenes never quite goes away. Subconsciously, people know that we are dealing with human monsters.

In my modest attempt at writing about the service nomads of globalism, I reflected upon how the Sephardim merchants of Amsterdam in the 17th century as Barbara Tuchman wrote in another context, offer a “distant mirror” that can be held up to the lives and issues faced by minority groups, in general, and Jews, specifically, today.

The ways in which the Sephardim grappled with the surrounding society, tolerance, the blending of cultures, and the limits of assimilation speak strongly to scholars confronting (or refusing to publicly confront, as the case may be) these very same issues in the modern world.

The economic and social opportunities for the Sephardim in 17th century Amsterdam presage the current discussions surrounding globalization and the formation and practice of identity politics and multiculturalism specific to Zionism and settler colonialism, in general.

If we use the “distant mirror” of history to study the positive factors that have allowed Jews and other minorities to live in productive harmony with their neighbors, we might achieve more than fighting anti-Semitism, racism, or even hate, in general.

Barbara Tuchman in Bible and Sword verifies that our some of our American forefathers were Protestant religious fanatics who claimed Judaism as their own. Some historians are quite well aware of all of this (but remain silent on the matter), most Jews are not. It was no secret — they flew the flag of Moses metaphorically, and culturally waged war with episcopal Christianity.

Protestantism has been partitioned greatly and is more divided theologically and ecclesiastically than the Catholic Church or Eastern Orthodoxy. Without any kind of unity in the Protestant Church, Christianity has been tremendously exploited for purely political purposes.

A theme throughout Tuchman’s work is the persistance of religion in politics, a seminal one that can only be addressed honestly —the importance and impact of religion.

During this pause sanitaire we have been afforded the wealthy opportunity of 20/20 vision, to see the turbulent political climate from a distant mirror of intellectual honesty.

During the stay at home time, I suggest checking out Practicing History: Selected Essays — Barbara Wertheim Tuchman. Tuchman presents ideas about history and how it should be written and then some of her actual writings are included to show why she is considered to be a master who rightly disagrees with trying to make history a science.

Narrative history is Barbara Tuchman’s medium—one which is not highly regarded in certain academic quarters. Her writing tells a story, because as she says, “human behavior is timeless."